— from Part II of the Catholics & American Life Symposium. New Oxford Review. January-Febuary 2025.

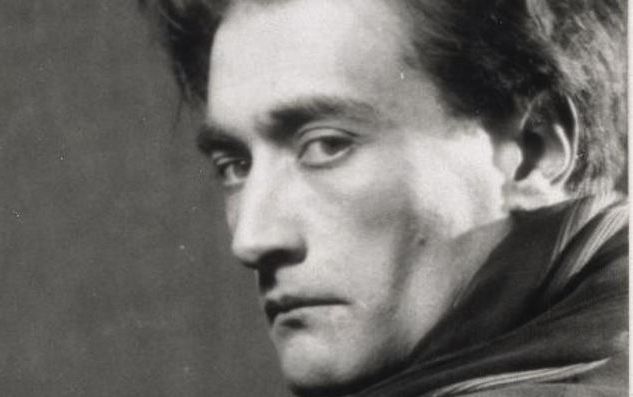

On Christmas Day 1886, 18-year-old Paul Claudel — raised Catholic but delinquent in his faith — was listening to vespers in Notre-Dame de Paris. It was an event that “dominates my entire life,” he later recounted.

“My heart was touched, and I believed. I believed with such a strength of adherence, with such an uplifting of my entire being, with such powerful conviction, with such a certainty leaving no room for any kind of doubt, that since then all the books, all the arguments, all the incidents and accidents of a busy life have been unable to shake my faith.”

Claudel would go on to a long diplomatic career, becoming the French consul in many countries and eventually ambassador to Japan and, from 1928 to 1933, to the United States. He achieved fame as a poet and playwright, but he was not yet famous when, in 1907, he received a letter from 20-year-old Jacques Rivière.

The young man was in a sorrier state, religiously, than Claudel had been before his 1886 reversion. Rivière was full of passion and doubt. “I seem to see Christianity dying,” he wrote. “Indeed, none of us know what has happened to it. Nor what to make of those spires above the roofs of our great towns which symbolize no longer the prayer of any of us…. Nor what those stucco crosses, disfigured by an abominable art, that stand above the graves in our cemeteries, would tell us.” Rivière was lost and ardently wished to be found. He and Claudel exchanged letters for years, Rivière asymptotically coming closer to peace with the Church and then veering off, repeatedly, into despair. He became a noted writer, editor, and critic. He never settled comfortably in the faith — his was a perpetually incomplete conversion — and he died of typhoid in 1925.

Well before he wrote his first, plaintive letter to his hero Claudel, Rivière was infected by that French philosophical malaise that produced so many fine but dead-end writers in the late-19th and early 20th centuries. He never acted sufficiently on Claudel’s superb advice to him: “Read Dante. And as much as you can find of Newman.” And Chesterton, whom Claudel greatly admired.

I mention Claudel and Rivière at length because they symbolize the hope and (seeming) hopelessness of our current ecclesiastical and political situations. Claudel shows the possibility of a quick and lasting change, Rivière the possibility of prolonged indecision and inertia.

Sometimes I say, in private or in public, “I’m an optimist. I’m positive that things will get worse.” The quip elicits a chuckle — or at least a smirk. Both sides of the comment are true. I do think things will get worse, in certain ways and in the short term, but I also think “this too shall pass.” Though I do not expect to live long enough to see Churchillian sunlit uplands, I may live long enough to be able to say, with a knowing smile, “I told you so.”

At times I share the frustration and pessimism of Rivière, at other times the calm and assurance of Claudel. Mostly I am with the latter. I do think some things will get worse — perhaps uncomfortably worse — but I have enough confidence in providential superintendence that I expect the worsening to be countervailed by a bettering. I am old enough to have seen sufficient examples.

Though I never saw it firsthand — I have lived in Southern California rather than in the South — I remember racial segregation. I remember when it was disappearing, with glacial slowness. We had the sense that its final demise would occur, but only in the distant future. And then, in a generation, it was gone, along with all sympathy for it. It wasn’t so much that the laws had changed but that hearts and minds had changed, more quickly than most people expected. I have seen parallel things in matters of religion.

I worked in Catholic apologetics for more than four decades and still dabble in it. I engaged lifelong anti-Catholics in public debates, and I dealt one-on-one in private with countless diehard opponents of the Church, both religious and secular. I dealt with Catholics more lukewarm than Rivière and more misinformed than Internet pundits. I learned much through these interactions, including not to despair. I have seen too many conversions — religious, civic, cultural — for that. Some have been gradual, others instantaneous. Many have been inexplicable, yet they occurred. I learned not to put my trust in princes, whether ecclesiastical or political, because they almost invariably disappoint.

I am skeptical of schemes, no matter how well reasoned or intentioned. I particularly am averse to sentimentalistic or romantic schemes, because of their impracticality. For that reason, I give little attention to, for example, the Catholic integralist movement. Though its logic may cohere — “Who says A must say B,” said Lenin — there is no real chance of its coming into play, at least not in this century. You cannot have a Catholic integralist society unless the society already is overwhelmingly Catholic — and convictedly so. In our wildest hopes, we are nowhere near that. The solution to current woes will need to be found elsewhere.

But I have misspoken, because there is no solution, at least not here below. There is only amelioration. Perhaps I have undiscovered British genes: I think we can muddle along, deleting much, repairing much, not despairing, but not fantasizing.

Karl Keating, a Contributing Editor of the NOR, has engaged in Catholic apologetics for more than four decades and is the author of 20 books. His most recent is 1054 and All That: A Lighthearted History of the Catholic Church.