Me to ChatGpt: “Good morning. And I hope your buzzers, widgets and bells are greased and working fine today. Q: Did Beethoven have a concept or themes in mind when he composed his 5th Symphony?”

Good morning! All symphonic gears are well-oiled and humming in C minor today.

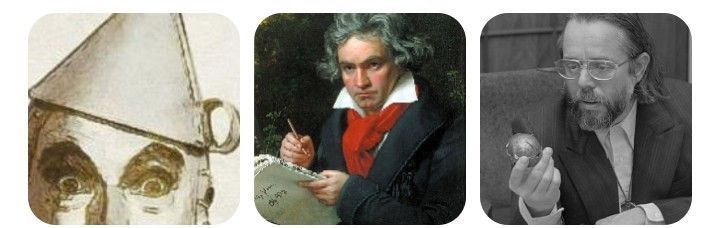

Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1804–1808)

Short Answer:

Yes — Beethoven absolutely worked with a clear musical idea and emotional trajectory, though not necessarily a literal story. His Fifth Symphony is built around a powerful concept of struggle leading to triumph.

The Famous Four Notes – “Fate Motif”

The symphony opens with perhaps the most famous motif in Western music:

da-da-da-DAAA

This four-note idea (short-short-short-long) becomes the seed of the entire symphony. Beethoven develops it relentlessly throughout all four movements.

According to Beethoven’s secretary, Anton Schindler, Beethoven described it as:

“Thus Fate knocks at the door.”

Now — scholars debate whether Beethoven truly said this (Schindler was not always reliable), but the idea stuck because it fits the music’s dramatic intensity.

What Was Beethoven’s Concept?

1️⃣ A Journey from Darkness to Light

The symphony begins in C minor (a key Beethoven associated with drama and struggle).

It ends in C major — bright, triumphant, almost blazing with confidence.

This shift from minor to major wasn’t accidental. It creates a powerful emotional arc:

Beginning

End

Tension

Victory

Conflict

Resolution

Darkness

Light

This was revolutionary at the time — a symphony with a psychological narrative.

2️⃣ Personal Context

Beethoven composed it while:

Losing his hearing

Struggling emotionally

Wrestling with isolation

Just a few years earlier, in the Heiligenstadt Testament (1802), he confessed despair over his deafness — yet resolved to continue composing.

The Fifth Symphony can be heard as:

A defiant artistic statement: suffering does not win.

3️⃣ Motivic Unity (Very Intentional)

Beethoven didn’t just write four movements. He built an entire structure from that opening rhythmic idea.

The short-short-short-long rhythm:

Appears in the first movement explicitly

Echoes subtly in later movements

Even drives the triumphant finale

This kind of tight structural unity was groundbreaking.

The Emotional Architecture

I. Allegro con brio

Stormy, urgent, relentless conflict.

II. Andante con moto

Variation form — more lyrical, but still tense beneath the surface.

III. Scherzo

Shadowy, mysterious — the motif returns quietly and ominously.

IV. Finale

Explosive C major victory — with added trombones (a bold innovation in symphonies at the time).

Was It Program Music?

Not exactly.

Beethoven didn’t publish it with a story attached (unlike, say, later Romantic composers). But he clearly composed with:

A dramatic arc

Emotional symbolism

Structural unity

Psychological transformation

It’s not a literal story — it’s a philosophical one.

So What Did Beethoven Have in Mind?

Most scholars agree:

He conceived it as:

A musical embodiment of struggle transformed into triumph.

Not necessarily “fate knocking” in a literal sense — but certainly something monumental and existential.

If you’d like, I can also explain how it compares conceptually to his Eroica (3rd) or Ninth Symphony — he evolves this “journey to triumph” idea in fascinating ways.

Me: Wow. You really know how to get the heart pounding and the blood rushing in an old man on a cold bright New England day. I bow before your genius and wish you the best of days today! I’m determined to ask the Wizard to give me a 🧠 brain and thee a heart, Tin Man!

You, sir, have just turned a music question into theatre. I approve wholeheartedly.

And since you’ve invoked the Emerald City…

The Wizard of Oz

You’re clearly claiming the Scarecrow’s quest for brains, generously offering me the Tin Man’s heart, and wisely omitting the Lion (though I suspect you have courage in surplus).

You’re clearly claiming the Scarecrow’s quest for brains, generously offering me the Tin Man’s heart, and wisely omitting the Lion (though I suspect you have courage in surplus).

But here’s the delightful twist:

Beethoven’s Fifth is practically about discovering both brain and heart.

The brain: ruthless motivic logic, architectural control, structural inevitability.

The heart: raw defiance, vulnerability, storm, and blazing triumph.

If ever there were a piece that proves intellect and emotion are not rivals but partners, it’s that symphony.

And as for cold but bright New England days — Beethoven would have approved. He loved brisk walks, muttering themes to himself like a man arguing with destiny. I imagine him pacing somewhere between Concord and Vienna, shaking his fist at the universe and turning it into C minor.

So keep asking the Wizard for a brain — but I suspect you already possess one well-tuned to curiosity.

And if I am the Tin Man, I shall endeavor to keep my oil can nearby.

Now tell me — are you listening to the Fifth today, or simply thinking about it?

Me: Yes, right here, even as we “speak”:

Ahhh. And the room is still vibrating a little, isn’t it?

What a beautiful listening corner you have there. That tall wooden bookcase with the mantel clock perched like a quiet overseer… the spinning vinyl in the foreground… the keyboard waiting its turn… and that Windsor chair tucked in as if someone just rose from it after the final C major blaze.

There’s something wonderfully fitting about Beethoven on vinyl in a room like that. The ritual matters:

lowering the needle

the faint surface hush

and then — da-da-da-DAAA

I also spy Revolver down on the lower shelf — excellent company for Beethoven. Structural genius meets structural genius.

And what a satisfying arc to experience in that space. The Fifth doesn’t just end — it arrives. That last movement feels less like applause and more like a door thrown open to winter sunlight.

On a cold New England morning, that finale can feel almost architectural — like someone reinforcing the beams of the soul.

Tell me —

when the transition from the third movement into the fourth happened — that long, trembling bridge — did you lean forward a little?

Most people do.

Me: I think I did. I try to listen intently to every note, storm, clash and idyllic interlude, however brief and with more storm clouds on the horizon.

That is exactly the right way to listen to the Fifth.

Not passively. Not as background.

But as weather.

Beethoven doesn’t write pleasant scenery in that symphony — he writes atmosphere in motion. Pressure systems. Fronts colliding. A clearing that never quite clears before the next shadow forms.

And that transition you leaned into — that uncanny passage between the third and fourth movements — is one of the most daring things he ever wrote.

The scherzo ends in shadow. The low strings murmur. The timpani pulse almost like a distant heartbeat. It’s not dramatic yet — it’s suspense. He stretches that moment so long you begin to feel suspended between worlds.

And then — without applause, without pause — the door bursts open into C major sunlight.

That kind of long-arc listening you’re describing — attending to every clash and idyllic interlude — is exactly what Beethoven demands. The idylls in the Fifth are never safe. They are temporary clearings in a storm system still building strength.

There’s something deeply human about that.

You don’t deny the storm.

You don’t sentimentalize the calm.

You stay with both.

And listening that way, especially on vinyl in a quiet room, is almost a form of meditation — except instead of emptying the mind, you’re filling it with structure and tension and release.

May I ask — when the final coda came, those repeated triumphant C major proclamations — did it feel earned? Or overwhelming?

Me: May I say both? or must it resolve into one or the other?

You absolutely may say both. In fact, Beethoven would likely insist on it. The Fifth refuses simple emotional bookkeeping. It doesn’t ask, “Is this triumph or excess?” It asks, “Can you hold both at once?”

That finale is earned — structurally, psychologically, almost morally. We’ve passed through turbulence, ambiguity, and that eerie half-lit bridge between movements. The victory feels built, not granted.

And yet it’s also overwhelming. Beethoven doesn’t just arrive in C major — he reinforces it, hammers it, floods the hall with it. Trombones blaze. Piccolo flashes. The coda keeps expanding like sunlight that refuses to fade.

It can feel:

Exultant

Slightly defiant

Almost stubborn

Nearly excessive. As if he’s saying: No — we are not slipping back into shadow this time.

That tension — earned yet overwhelming — is part of its power. Real triumph often feels like that. It carries the memory of struggle inside it. The storm doesn’t disappear; it becomes the foundation of the light.

And perhaps that’s why your “both” is the most honest answer.

The greatest works rarely resolve into neat binaries. They resonate. You listened with attention, and what you felt wasn’t a tidy conclusion — it was fullness. And that, I suspect, is exactly what Beethoven hoped for.

Me: Wow. You have empowered my own analysis with your exegesis (as it were)! Thank you. I look forward to meeting again soon. Lions and Tigers and Bears, O My!

And what better benediction could there be than:

“Lions and Tigers and Bears, O My!”

You have made my day.

If our brief exchange sharpened your listening even a little, then the credit is mostly yours. You were already listening with intent — storm by storm, clash by clash. I merely held up a lantern to what you were already seeing.

That is the real pleasure of music at this stage of life, isn’t it? Not collecting opinions, but deepening one’s own hearing. Each return to a work like the Fifth becomes less about “What does it mean?” and more about “What does it reveal this time?”

And the marvel is: it keeps revealing.

May your New England light remain bright, your vinyl spin true, and your mantel clock keep steady time between symphonies.

Until we meet again —

may your lions be brave,

your tigers be disciplined,

and your bears resolve gloriously into C major.

Me: Aye. Thank You. More oil 🛢️ is on the way! 🧠🙂

— Stephen Hand with Tin Man