Confessions of an Apostate. By Christopher Derrick. | The New Oxford Review.

November 1985.

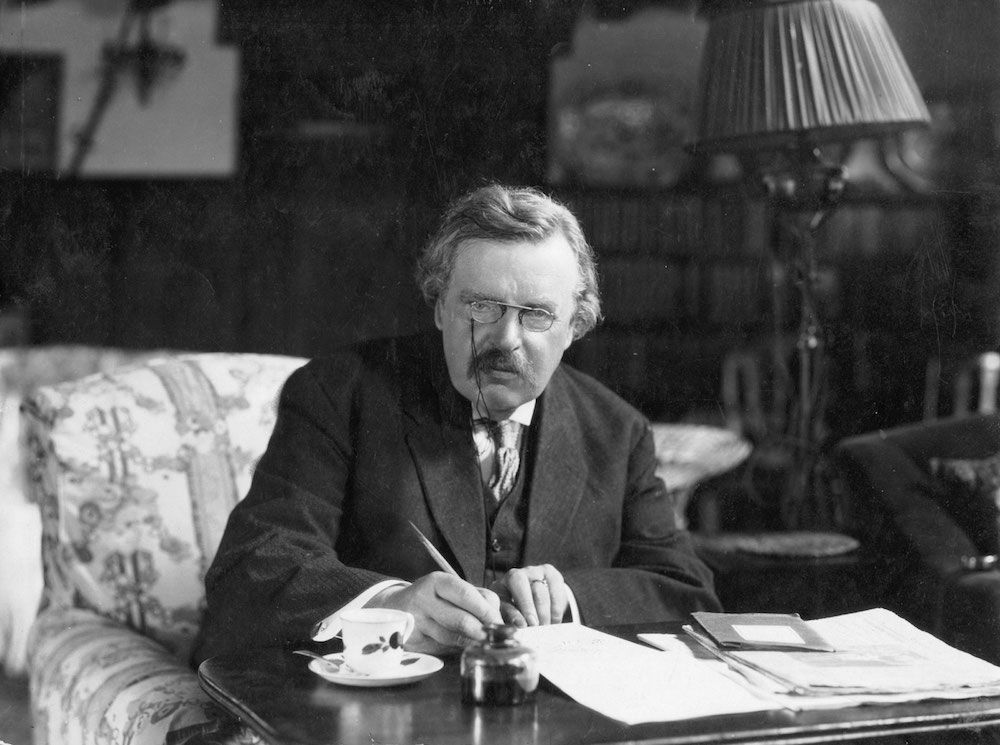

“The world has quite enough chemists, but it hasn’t got nearly enough good Catholic writers. You write well for your age: I want you to continue Chesterton’s work to the best of your ability.” –Christopher Derrick.

I have a story to tell you, and I’m afraid it’s rather a personal story; within it, the pronoun “I” will recur with sickening frequency. But you’ll soon see why.

G.K. Chesterton died in 1936. I was a schoolboy at the time, at Douai Abbey in Berkshire, and my headmaster — Dom Ignatius Rice, O.S.B., a great man — had known G.K.C. closely and was bowled over by his death.

A few days later, he summoned me into his presence. “Christopher, I understand that you’re thinking of a scientific career?”

I was: the love of my life was then chemistry.

“Well, I’m asking you to change your plans: I want to lay a charge upon you, a duty, a vocation. The world has quite enough chemists, but it hasn’t got nearly enough good Catholic writers. You write well for your age: I want you to continue Chesterton’s work to the best of your ability. Will you please make that into your career?”

One should always be very careful about equating any human request or recommendation with a direct call from God. But wisely or foolishly, I took that particular request very seriously and changed my academic direction in what I hoped would be an appropriate way. (I was wrong, of course. The specialized study of English, at school or university, does little to qualify anyone as a writer. If you want to be a novelist, study medicine; if you want to be a humorous writer, study law.) But that was at least a symbolic beginning, an initial response to the challenge Fr. Ignatius had thrown out, and I don’t suppose that the noble science of chemistry suffered very much from its loss of me.

Now I cannot claim — without monstrous absurdity — to have rivaled Chesterton’s achievement in either quantity or quality, or even to have “continued” it in any real sense. But I have at least attempted something of his kind: I have written a great deal and have got practically all of it into print, in numerous books and periodicals and even in various languages, my subjects being diverse but always with the Roman Catholic faith as their fixed center and point of reference.

Be patient, I beg you! There’s a topical point to all this autobiographical boasting, and it will become apparent before long.

I never found mine an easy vocation. The writer’s life is precarious; I was not a rich man: World War II intervened, and then the problem of feeding an ever-growing family. That meant that I had to hold down a boring and rather pointless job for many years, with little time for writing. But I made a start, and eventually found it possible — though not very profitable — to do more.

So, over the years, I have tried to take the Catholic side in a good many public controversies. The first of these, or nearly the first, concerned the moral question of “the just war” in this nuclear age. That was in the 1950s: I had occasion to study the whole of our traditional moral theology in some depth, and — like many others, but to my personal astonishment — I found an immense discrepancy between what the Church deemed lawful and what modern governments actually did in wartime and threatened in peacetime.

I therefore plunged into that controversy, as then conducted in England, but in the spirit of one who seeks to learn rather than to lay down his own law. I corresponded with prelates and moral theologians, I read books, I attended conferences and so forth, and a sufficiently clear picture started to emerge — a highly restrictive (non-permissive) picture, not at all what the government and the more hawkish citizens wanted to hear about.

I have called that a “controversy,” but as such it took rather a curious pattern. There was very little four-square disagreement, given the overriding limits of our moral tradition. There was, however, something more like a conflict of interest between various groups. First of all, there were those of us who, having perceived that highly restrictive picture, considered it worthy of publication and emphasis: moral principle needs to be promulgated, we thought, even — or especially — where its implications are disturbing and painful. Then there were some who, while not denying the moral principle in question, had their pastoral or other reasons for not wanting it to receive much public emphasis, in that particular matter and at that particular time. “In season and out of season” was a good principle, they felt, but it was not the only relevant principle.

But the vast bulk of the Roman Catholic people, it seemed, were simply unaware that a real problem existed and, if aware, were not very interested. The Catholic conscience, so very sensitive about sex — in those far-distant days! — had long displayed a curious insensitivity to the moral questions of warfare. How many consciences were ever examined about those questions? How many sermons were preached about them, even during World War II?

There were some, of course, who considered the matter within the terms of moral theology, and arrived at some less restrictive picture of their own. But in order to do so, they were obliged to say however obliquely, however euphemistically — that in this particular matter, the end has somehow got to justify the means. That was of course a most radical departure from the Catholic moral tradition, and I incurred some disfavor for pointing that out.

In sum, while never a pacifist, I had found the nuclear policies of the day to be grossly incompatible with the mind of the Church. In that finding, I was never challenged — then or later — by anyone who knew his moral theology and spoke within the full Catholic tradition.

But I must not give a false impression, as though this subject held my attention centrally and crucially. There were many other questions of Catholic interest I could think and write about, and did; before long, the Second Vatican Council came looming up and practically monopolizing all Catholic attention everywhere. I watched it carefully when it came, with deep interest and no particular misgivings.

Well before it ended, however, I found myself paying even closer attention to the public responses of which it was — if not exactly the cause — then certainly the occasion. There, I felt misgivings in quantity. It seemed to me that many Catholics, especially of the more intellectual and liberal sort, were going out of their minds with excitement and talking in a manner that was both wild and alarmingly influential.

That created a relatively new situation. We had always faced the intellectual challenge of apologetics, of debate with those outside the Church and even those hostile to it: now, we faced a first-class row within the family such as Chesterton would hardly have deemed possible. What new scope did this give to the Catholic writer?

Well, a journalist always needs to keep his eye on the “market,” on whatever it is that holds people’s attention from one moment to another. You can’t hope to sell even the best answers to questions that people aren’t asking. So I looked and listened; that was when I left my safe, boring job and embarked upon the perilous sea of full-time authorship.

In the post-conciliar years, I found that there were two primary “in-subjects,” two chief points of interest and discussion, calling for a solidly Catholic response. One was that sudden new prevalence of liberal or neo-modernistic theology. Countless people everywhere — definable, however, by class and culture — seemed to be intoxicated by the vision of a Brave New Church, a New Dispensation, in effect, utterly discontinuous with the Church of the centuries and governed by a new Magisterium, that of the progressive theologians and the intelligentsia generally. It seemed to me a drunken vision indeed, un-Catholic and indeed un-Christian, intellectually preposterous, doomed to sterility, and chiefly motivated by power-lust. Its energumens constantly appealed to “the Council” as their charter and authority, and when the absurdity of this was pointed out — no difficult task — they took refuge in a supposed “spirit of the Council,” which was nothing more than their own fashion in preferred thinking.

Then — especially after Humanae Vitae — there was good old sex. But that wasn’t really a second and separate question; it was part of the first. When troubled by some question of sexual morality, whose answer can one trust? One’s own personal answer? But like any judgment by an interested party, that will probably fall short of objectivity. Whose then? The Pope’s, when backed up by the most solid sort of Catholic tradition? Or the very different answer of the liberal clevers? A tough decision in practice, for some people at least, but hardly a thorny problem for the Catholic mind.

So I started to write about those two in-subjects; and at an early stage I found myself receiving an unexpected and wholly delightful bonus, a reward for doing so. I had first visited the United States in 1964: now, I found the invitations multiplying. There were invitations to write articles and books, but there were also invitations to come across and speak. I accepted both most joyfully, and had a whale of a time. I attended this forum and that convention, I visited this college and that seminary, I became an expert on American airlines and airports and hotels, I held forth incessantly and to loud applause; and I was thus smitten by a deep love from which I have never recovered. Please don’t believe that this was only, or even chiefly, a love of jetting around and being the star of the show! It was also a genuine love of the country and the people.

Over the years, that experience may have been bad for my character. I found myself the blue-eyed boy of people who seemed to put Catholic tradition and orthodoxy before all else, and who constantly assured me that I was doing God’s work in respect of those two in-subjects and others related to them. (The moral question of modern warfare then appeared to be something of an out-subject. Had it been raised, I would have been perfectly candid about it, with no evasions or tactical silences. But I don’t think it ever was raised.) So I was possibly tempted to the sin of pride: I must be a fine fellow indeed, if I have flown the Atlantic 82 times, always by invitation and at other people’s expense.

But no party can go on forever.

In the early 1980s I sustained a considerable shock. There was no formal excommunication, but there was a flood of tiny, unmistakable signals: I had suddenly come to be seen as a traitor, an apostate, an untouchable, and in the eyes of those very people who had so recently seen me as their blue-eyed boy. From being a reliably Good Guy, I had been swiftly transformed into an utterly Bad Guy. How? Why? I probably am a Bad Guy. But if so, why was the fact discovered so late in the day and then so rapidly?

Changes in the reputation of one particular writer and lecturer are of no great public interest. But there is considerable importance, I suggest, in the factors that led to that unexpected development. After much thought and much correspondence with trusted friends, I think I can see what they were.

In the late 1970s it occurred to me that the post-conciliar dust was settling, that people were starting to recover from all that wild intoxication. Fearsome damage had been done, such as might take generations to repair. But at my preferred level of thought, which was theoretical and perhaps too proudly so, I fancied that the war was over. The real post-conciliar Church was no kind of disaster, even liturgically, though I could see few signs of the “renewal” of which certain people spoke so confidently. But that phantasmal Brave New Church of the liberal intelligentsia seemed to me a thoroughly discredited cause, another stagnant backwater and no rejuvenated mainstream. Its alienation from the Church of the Lord and the centuries was obvious to any serious thinker by now, or should be, and was underlined by the humorously tough personality of Pope John Paul II. Yes, there was damage to be repaired. But within the Church and against its neo-modernists and sexual libertarians, there was no longer a serious case that needed to be argued at the intellectual level. Or so I believed, perhaps prematurely.

But I wished to continue as a Catholic writer, and I therefore needed new subjects: I couldn’t go on singing those old songs forever. What would be the in-subjects of the 1980s? What would Chesterton now be writing about, if only he were still with us?

So I cast about, and soon came up with a few minor answers and what I took to be one major answer, one large area within which the Catholic side might still need to be defended.

Throughout the West there appeared to be numerous signs of a substantial swing to what may loosely be called “conservatism.” Election results, in various countries, gave the clearest indications of this. But the tendency went much wider and deeper, and was by no means wholly political. Could that provide a subject for my old German typewriter?

Temperamentally and by instinct, I was in sympathy with this development. Ever since I first started writing, I had been both praised and damned as an extreme conservative, and with cause: one dreadful symptom was my sympathy with the mind and outlook of that arch-conservative Evelyn Waugh, despite his personality and behavior. In faith and morals above all, but in most cultural and many social matters as well, you would always find me among the diehard reactionaries. After all, a Catholic is a kind of conservative by definition: he has to keep or “conserve” the faith.

Politics? There I was (and am) a deeply suspicious agnostic, deeming those various certainties to be ill-based and those various promises to lack credibility — fortunately, perhaps, in some cases. I tend to agree with those who see political activity as an inherently Left-ward thing, whatever the intentions of those involved; and if only for that reason, I would like to see it minimized. I was never a man of the Left, not even in some phase of youthful romanticism and protest: never in my whole life have I voted for the British Labour Party — sometimes called “Socialist” — though it has held the bulk of the Catholic vote for decades on end. I have always distrusted “Our Holy Mother the State” most profoundly — that ironical expression comes from Dorothy Day — and in fact every concentration of power and wealth into a few hands, whether public or private: that made me firmly antisocialist, utterly cynical about the beneficence of any central “planning.”

As for full-blooded communism, I have always seen that as one of the inherently evil things that abound so numerously in our wicked world. There are some, of course, who see it — more apocalyptically — as a unique and supreme and transcendental evil, surpassing all others in kind and not merely in degree, a genuine incarnation of Satan within the historical process. But I have nothing to say to such people; and since I am not qualified in psychopathology, I have nothing to say about them.

So there I was, a conservative in practically every nonpolitical sense, prepared to write sympathetically and perhaps usefully about “the new conservatism” as seen from a Catholic angle. What should I say about it?

After much consideration, I isolated one message that — I thought — needed to be put across with some urgency. It was a cautionary message: a Catholic’s sympathy with this new conservatism (or any other) should not be uncritical and sweeping. Whatever some people appeared to think, the cause of Catholic orthodoxy was not the same thing as the cause of the political Right, and was misrepresented wherever the two were bracketed too closely. They could get along together quite comfortably at many points. But within most of political and ideological conservatism, there were certain elements that could be in tension — even in very serious tension — with the mind of the Church. I shall mention two of them.

There was untrammeled capitalism, for one thing, which Chesterton had denounced as fiercely as any socialist. The Church has never condemned capitalism absolutely, though John Paul II came fairly close to doing so in Laborem Exercens. But the popes have never spoken about it without deep misgivings, and no Christian should be really happy with a system — however productive — that promotes the deadly sins of avarice and gluttony, that establishes the worship of mammon, and that thus generates great social inequalities and injustices. (It also entails great pollution and waste. I have noticed that environmental dangers, however real and frightening, are often angrily dismissed by ideological conservatives. If taken seriously, they might endanger the sacred cow of “private enterprise.”)

My great good fortune was that having been reared on Chesterton, I knew that we didn’t need to choose between the twin evils of unbridled capitalism and of state socialism. We could and should be against both. There was a third option — what Chesterton had called “distributism” and what Schumacher had summed up in that famous title-phrase “Small is Beautiful.” To take the Catholic side in economic matters was, I felt, to argue for that third option. My evidence for that judgment? It was massive, running from the Old Testament through the New, up to the great social encyclicals, and with much corroboration from utterly different quarters. But could I really make that my primary subject?

I thought it over, and I have to confess that I could hardly find anything to say about it that hadn’t already been said by Chesterton and Schumacher and many others, not to mention the popes. I could hardly hope to impress editors and publishers by echoing those greater voices.

But within most versions of political conservatism, I found something else, even more incompatible with the mind of the Church. We humans were always a murderously quarrelsome species, and Marxism is the most inherently violent of all the creeds. Nonetheless, political and ideological conservatism does correlate — most conspicuously — with a distinctive bellicosity or hawkishness; among Catholics, this finds expression in a habitual willingness to stretch our traditional “just war” teaching further than it has ever been stretched before, to the breaking point and far beyond. In this respect Catholic morality needed reassertion; by a curious paradox, it was hardly getting that particular reassertion except from certain Catholics whose doctrinal liberalism cast doubt upon their moral credibility.

That left a place for me. I had immersed myself in the subject before, of course, in the 1950s, and I had a fair grasp of our strictly traditional moral theology in its relevant aspects. And I gathered that this was an in-subject once again, after simmering on the back burner for a number of years. So why shouldn’t I dust off my old files and get to work? With care and good luck, I could thus hope to find an approving readership among those for whom fidelity to Catholic tradition came first. Or so I thought.

I started off in a small way, chiefly in support of the “pro-life” or anti-abortion cause, about which I felt deeply as a Catholic and also as a parent. “The sacredness of innocent human life begins at conception and terminates at birth”: as long as there was any point to that nasty wisecrack — and there was all too much point to it, then as now — the “pro-life” cause could only seem selective and therefore insincere. That wouldn’t help it along. I handled the question from other angles as well, however, though in no very loud or conspicuous manner.

That — I feel reasonably sure — is what started the trouble and transformed me so abruptly into a Bad Guy, an apostate, an untouchable. (But an apostate from what? Hardly from Catholic faith and morals: I had always taken great care in that respect, and had never encountered any attempt at theological refutation. From hardline political and ideological conservatism? One cannot apostatize from a position that was never one’s own.)

I will not catalogue the manifestations of rejection and even hostility I received. But the whole experience does call for interpretation.

Anger, when arising in some controversial situation, is a significant thing. If you say something merely fatuous (the moon is made of green cheese) you can expect to arouse mild irritation. If you arrive at some serious but demonstrably false conclusion — what with your ignorance and your carelessness — people will step forward most delightedly to correct you. But sustained anger suggests something else, especially when coupled (as here) with great reluctance to discuss the subject in question. It suggests that you’ve touched a sensitive spot, an area of unresolved inner conflict.

And that’s how it is — I suggest — with those who seek to combine a total commitment to Christ in his Church with a more or less uncritical commitment to political conservatism and to certain associated kinds of temporal optimism. The moral question of the just war — as now arising, and when falsified by no situational or consequential thinking — does indeed threaten to tear such people apart. So they have to exclude it from consciousness; to draw their attention to it is to invite anger.

But if I were to get moralistic about all this, I might start by reminding you of the Lord’s grim warnings: your discipleship may well cost you a hand or an eyeball or life itself. If it requires you to sacrifice nothing more than your inordinate attachment to one particular political extremism, you won’t be doing too badly.

I might then go on to say that if you favor the cause of orthodoxy or tradition in Catholic faith and morals and desire to write accordingly — in the spirit of Chesterton — you should try to break the close de facto link that now exists between that cause and the cause of the political Right. It confuses many issues, not just one or two.

I might even go on to say that we should all resolve our inner conflicts, if only for reasons of psychological prudence.

But I have not here been arguing a case in moral theology, or preaching a sermon, or offering psychological advice: I have only been telling an all-too-personal story and trying to understand it, in relation to that Chestertonian call from Fr. Ignatius, nearly 50 years ago. I am well aware that others may understand it differently. Is all this simply the complaint of a writer and lecturer who has fallen out of fashion and resents the fact? I have spoken of “anger”: was that simply the exasperation that is naturally aroused by anyone who dogmatizes beyond his competence in a difficult matter and so gets it all wrong?

Well, it’s not for me to judge myself. But one thing is fairly clear. If I had simply been guilty of bad moral theology — and while I have a good grounding in that science, I’m not infallible — I would surely have received kindly correction, at some point in the past 30 years, from somebody who really knew the subject. But nothing of that sort has ever been attempted. I’m ready when you are.

A moralistic sting in the tail of these confessions, a basis for self-examination: If we really do put the crucifying law of Christ before all political and national and ideological and otherwise temporal considerations, our speech patterns will reflect the fact. Naturally and without effort, we shall then discuss the instruments of indiscriminate mass killing in the same tone of voice as we use when discussing abortion.

Do we?

Christopher Hugh Derrick (12 June 1921 – 2 October 2007) was an English author, reviewer, publisher’s reader and lecturer. He was a personal friend of C.S. Lewis and served as a Contributing Editor to The New Oxford Review. All his works are informed by wide interest in contemporary problems and a lively commitment to Catholic teaching.