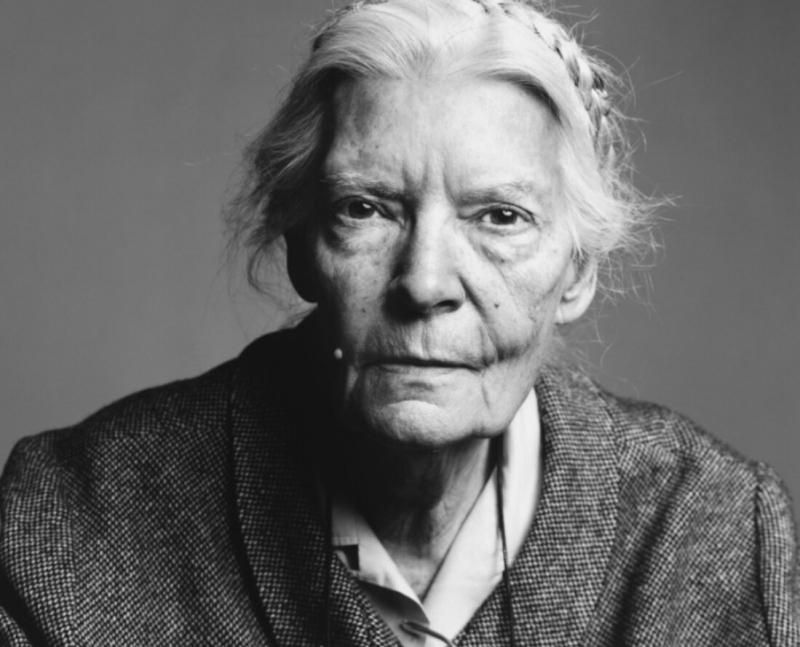

By Dorothy Day.

We must begin sometime to aim at sanctity. The tragedy, Newman said, is never to begin. Or having put one’s hand to the plough, to turn back. To become a tired radical. To settle down to relish comfortably past performances of self-sacrifice and self-denial. It is not enough, St. Ambrose remarks, to leave all our possessions, we must also follow Him, and that means to the Cross, to Gethsemane and Calvary, before one can share in the Resurrection and Ascension. “I die daily,” St. Paul said, and I’ve often thought it was not the big struggles, the great deaths we have to undergo that are so hard, as the daily torture of denying oneself, mortifying, putting to death the old man in us. Thank God a good part is done for us. . . .

Seven years have passed since the beginning of the basic retreat, and we have died many deaths, and many sorrows have entered our lives. Not only the tragedy of a great war, a cataclysm that brought with it the atom bomb and an apocalyptic attitude toward life, but also all the small tragedies which make up our lives. . . . the daily tragedies of life, of poverty, and loss of love, and sickness and death, striking in our midst; these are the sorrows and pain incident to dying daily, to putting off the old man and putting on Christ.

Dying is not pleasant. Dying is painful. We have to accept the Cross, take up our Cross, and die to rise again. It is growth, normal growth, and if the egg does not proceed in due course to become a chick and put on wings, it becomes a destroyed egg.

Youth demands the heroic, Claudel says, and the heroic is the tragic, and the glorious, the laying down one’s life for one’s brother, the losing it to save it, the following of Christ, not just the giving-up of possessions. Youth in this era has begun to know about what the heroic is, and has through war and revolution endured sacrifice, poverty, cold and hunger, grim pain and imprisonment, loss of all worldly goods.

We cannot deny the heroism of the world, of countless thousands of those who took part in the last gigantic slaughter [WWII], of men and women who laid down their lives, “who gave their all.” And despite the exalted mouthings of hired writers for the government, we know with that we would be happy if we were as sure of our courage as the unknown and unsung heroes throughout the world that have risen up in this day. But we know too, that heroism can go much further, that there is a martyrdom of the inner senses, the understanding and the will; that until we see the kenotic aspects of Christ’s life, the humiliations of his manhood, the scorn heaped upon him; until we understand how little he thought of worldly honor and prudence, we have not yet begun to “put on Christ.” —- from Spiritual Writings, edited by Robert Ellsberg

SAINTS AS THEY REALLY WERE

Robert Ellsberg writes, “Soon after her conversion, Dorothy began to read more about saints. She always distinguished between “saints as they really were” and the representations of pious hagiography.” She wrote,

At that time I did not understand that we are all “called to be saints,” as St. Paul puts it. Most people nowadays, if they were asked, would say diffidently that they do not profess to be saints, indeed they do not want to be saints. And yet the saint is the holy man, the “whole man,” the integrated man. We all wish to be that. But in these days of stress and strain we are not developing our spiritual capacities as we should and most of us will admit that. We want to grow in love, but we do not know how.

Love is a science, a knowledge, and we lack it. Thérèse

…We are called to be saints—we are the sons of God! This blindness of love, this folly of love—this seeing Christ in others, everywhere, and not seeing the ugly, the obvious, the dirty, the sinful—this means we do not see the faults of others, only our own. We see only Christ in them. We have eyes only for our beloved, ears for His voice. But it is all “to make their point,” as Peter Maurin would say. The saints rose above the natural, the human, and became supernatural and superhuman in their love. Nothing was too difficult for them, all was clear, shining and beautiful on the pathway of love.

Everyone is Christ. June 1944

In all secular literature it has been so difficult to portray the good man, the saint, that a Don Quixote is made a fool and the Prince Myshkin [in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot] an epileptic, in order to arouse the sympathy of the reader, appalled by unrelieved goodness. There are, of course, the lives of the saints, but they are too often written as though they were not in this world. We have seldom been given the saints as they really were, as they affected the lives of their times—unless it is in their own writings. But instead of that strong meat we are too generally given the pap of hagiography. Too little has been stressed the idea that all are called. Too little attention has been placed on the idea of mass conversions. We have sinned against the virtue of hope. There have been in these days mass conversions to Nazism, fascism, and communism. Where are our saints to call the masses to God?

Personalists first, we must put the question to ourselves. Communitarians, we will find Christ in our brothers.

As a convert, I never expected much of the bishops. In all history popes and bishops and Father Abbots seem to have been blind and power loving and greedy. I never expected leadership from them. It is the saints that keep appearing all thru history who keep things going. What I do expect is the bread of life and down thru the ages there is that continuity. Living where we do there certainly is no intellectual acceptance of the Church, only blind faith. I mean among the poor. The gospel is hard. Loving your enemies, and the worst are of our own household, is hard…

St. Joseph

Today as I write it is the feast of St. Joseph, our particular patron, since we too have been so hard put to find shelter not only in New York but in other cities where we have houses of hospitality. We have always looked to him as to one who found a home, poor as it was, for Mary and the holy Child. He is a model for the worker, for the craftsman, for the husband and father, and we beg him most especially to guard our newly acquired house on East First Street, named for him. Hideous violence broke out only a few doors away from us this last week between two motorcycle gangs and resulted in the death of one unidentified youth who was found bound and burned to death in a tenement apartment. St. Joseph, pray for us all.

And pray that the spirit of penance will strengthen us to overcome hatred with love. Drug addiction results in such tragedies, and with many alcohol itself is an addiction. To help our brothers let us do without what maddens the heart of man only too often. Drugs are a good to alleviate pain, and on festivals wine gladdens the heart of men. But we see too much of tragedy.

Have pity, have pity on the poor around us, and fast from the unnecessary that the destitute may have more. March 1969

St. Francis

St. Francis was “the little poor man,” and none was more joyful than he; yet he began with tears, with fear and trembling, hiding in a cave from his irate father. He had expropriated some of his father’s goods (which he considered his rightful inheritance) in order to repair a church and rectory where he meant to live. It was only later that he came to love Lady Poverty. He took it little by little; it seemed to grow on him. Perhaps kissing the leper was the great step that freed him not only from fastidiousness and fear of disease, but from his attachment to worldly goods as well. Sometimes it takes but one step. We would like to think so. And yet the older I get the more I see that life is made up of many steps, and they are very small affairs, not giant strides. I have “kissed a leper,” not once but twice—consciously—and I cannot say I am much the better for it. The first time was early one morning on the steps of Precious Blood Church. A woman with cancer of the face was begging (beggars are allowed only in the slums), and when I gave her money (no sacrifice on my part but merely passing on alms which someone had given me) she tried to kiss my hand. The only thing I could do was kiss her old face with the gaping hole in it where an eye and a nose had been. It sounds like a heroic deed, but it was not. One gets used to ugliness so quickly.

What one averts one’s eyes from one day can easily be borne the next when we have learned a little more about love. Nurses know this, and so do mothers.

Another time I was refusing a bed to a drunken prostitute with a huge, toothless, rouged mouth, a nightmare of a mouth. She had been raising a disturbance in the house. I had been remembering how St. Thérèse said that when you had to say no, when you had to refuse anyone anything, you could at least do it so that they went away a bit happier. I had to deny her a bed, but when that woman asked me to kiss her, I did, and it was a loathsome thing, the way she did it. It was scarcely a mark of normal, human affection.

We suffer these things and they fade from memory. But daily, hourly, to give up our own will and possessions, and especially to subordinate our own impulses and wishes to others—these are hard, hard things; and I don’t think they ever get any easier. . . .

Peter Maurin, Co-founder Catholic Worker

Peter was the poor man of his day. He was another St. Francis of modern times. He was used to poverty as a peasant is used to rough living, poor food, hard bed, or no bed at all, dirt, fatigue, and hard and unrespected work. He was a man with a mission, a vision, an apostolate, but he had put off from him honors, prestige, recognition. He was truly humble of heart, and loving. Never a word of detraction passed his lips and, as St. James said, the man who governs his tongue is a perfect man. He was impersonal in his love in that he loved all, saw all others around him as God saw them. In other words he saw Christ in them.

He never spoke idle words, though he was a great teacher who talked for hours on end, till late in the night and early morning. He roamed the streets and the countryside and talked to all who would listen. But when his great brain failed, he became silent. If he had been a babbler he would have been a babbler to the end. But when he could no longer think, as he himself expressed it, he remained silent. For the last five years of his life he was this way, suffering, silent, dragging himself around, watched by us all for fear he would get lost, as he did once for three days; he was shouted at loudly by visitors as though he were deaf, talked to with condescension as one talks to a child to whom language must be simplified even to the point of absurdity. That was one of the hardest things we had to bear, we who loved him and worked with him for so long—to see others treat him as though he were simpleminded. The fact was he had been stripped of all—he had stripped himself throughout life. He had put off the old man, to put on the new. He had done all that he could to denude himself of the world, and I mean the world in the evil sense, not in the sense that “God looked at it and found it good.” He loved people, he saw in them what God meant them to be. He saw the world as God meant it to be, and he loved it.

He had stripped himself, but there remained work for God to do. We are to be pruned as the vine is pruned so that it can bear fruit, and this we cannot do ourselves. God did it for him. He took from him his mind, the one thing he had left, the one thing perhaps he took delight in. He could no longer think. He could no longer discuss with others, give others, in a brilliant overflow of talk, his keen analysis of what was going on in the world; he could no longer make what he called his synthesis of cult, culture and cultivation. He was sick for five years. It was as though he had a stroke in his sleep. He dragged one leg after him, his face was slightly distorted, and he found it hard to speak. And he repeated, ’’I can no longer think.”

When he tried to, his face would have a strained, suffering expression. No matter how much you expect a death, no matter how much you may regard it as a happy release, there is a gigantic sense of loss. With our love of life, we have not yet got to that point where we can say with the desert father, St. Anthony, “The spaces of this life, set over against eternity, are brief and poor.”

Peter was buried in St. John’s Cemetery, Queens, in a grave given us by Fr. Pierre Conway, the Dominican. Peter was another St. John, a voice crying in the wilderness, and a voice too, saying, “My little children, love one another.” (ibid)