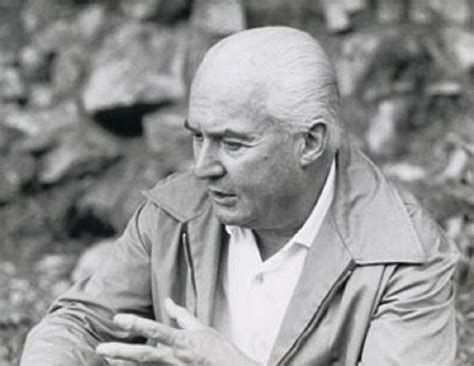

By Carlo Carretto, 1910 – 1988 (*).

Carlo Carretto PFE was an Italian Catholic and member of the Little Brothers of the Gospel. See other links at this website. His books can be purchased at Amazon.com.

~~~

“Charles de Foucauld said one day: “If the contemplative life were possible only behind monastic walls or in the silence of the desert we should, in fairness, give a little convent to every mother of a family, and a track of desert to every person working hard in a bustling city to earn his living.” The vision of the reality in which the majority of poor men and women live determined the central crisis of his life; the crisis which was to carry him far from his first understanding of the religious life.

As you may know, Charles de Foucauld was a Trappist, and had chosen the poorest Trappist monastery in existence, that of Akbès in Syria. One day his superior sent him to watch by the corpse of a Christian Arab who had died in a poor house.

When Brother Charles was in the dead man’s hovel he saw real poverty around him: hungry children and a weak, defenseless widow without assurance of the next day’s bread. It was this spiritual crisis which was to make him leave La Trappe(1) and go in search of a religious life very different from the earlier one.

“We, who have chosen the imitation of Jesus and Jesus Crucified, are very far from the trials, the pains, the insecurity and the poverty to which these people are subjected. “I no longer want a monastery which is too secure. I want a small monastery, like the house of a poor workman who is not sure if tomorrow he will find work and bread, who with all his being shares the suffering of the world. Oh, Jesus, a monastery like your house at Nazareth, in which to live hidden as you did when you came among us.”

Sahara. 1954 – 1965

When he came out of La Trappe Foucauld founded his first fraternity at Beni-Abbès in the Sahara; later he built his hermitage at Tamanrasset where he died, murdered by the Tuareg.

The fraternity was to resemble the house of Nazareth, a house just like one of the many houses one sees along the many streets of the world. Had he renounced contemplation then? Had his fervid spirit of prayer weakened? No, he had taken a step forward. He had decided to live the contemplative life along the streets, in a situation similar to that of any ordinary man. That step is much harder! It is a step that God wants humankind to make.

The life of Charles de Foucauld opens up a new understanding of the spiritual life in which many will force themselves to make the fusion between contemplation and action—really living and obeying the first commandment of the Lord, “Love God above all things and your neighbour as yourself.”

“Contemplation in the streets.” This is tomorrow’s task not only for the Little Brothers, but for all the poor. Let us begin to analyze this element of “desert” which must be present, especially today, in the carrying out of such a demanding program. When one speaks of the soul’s desert, and says that the desert must be present in your life, you must not think only of the Sahara or the desert of Judea, or into the High Valley of the Nile. Certainly it is not everyone who can have the advantage of being able to carry out in practice this detachment from daily life. The Lord conducted me into the real desert because I was so thick-skinned. For me, it was necessary. But all that sand was not enough to erase the dirt from my soul, even the fire was not enough to remove the rust from Ezekiel’s pot. But the same way is not for everybody. And if you cannot go into the desert, you must nonetheless “make some desert” in your life.

Every now and then leaving men and looking for solitude to restore, in prolonged silence and prayer, the stuff of your soul. This is the meaning of “desert” in your spiritual life.

One hour a day, one day a month, eight days a year, for longer if necessary, you must leave everything and everybody and retire, alone with God. If you don’t look for this solitude, if you don’t love it, you won’t achieve real contemplative prayer. If you are able to do so but nevertheless do not withdraw in order to enjoy intimacy with God, the fundamental element of the relationship with the All-Powerful is lacking: love. And without love no revelation is possible. (Emphasis added).

But the desert is not the final stopping place. It is a stage on the journey. Because, as I said, our vocation is contemplation in the streets. For me, this is quite costly. The desire to continue living here in the Sahara forever is so strong that I am already suffering in anticipation of the order that will certainly come from my superiors: “Brother Carlo, leave for Marseilles, leave for Morocco, leave for Venezuela, leave for Detroit. “You must go back among people, mix with them, live your intimacy with God in the noise of their cities. It will be difficult but you must do it. And for this the grace of God will not fail you.

“Every morning, after Mass and meditation, you will make your way to work in a store or shipyard. And when you get back in the evening, tired, like all poor men forced to earn their living, you will enter the little chapel of the brotherhood and remain for a long time in adoration; bringing to your prayer all that world of suffering, of darkness, and often of sin, in the midst of which you have lived for eight hours taking your share of pain and toil.”

Contemplation in the streets. A good phrase, but very demanding. Certainly it would be easier and more pleasant to stay here in the desert. But God doesn’t seem to want that. The voice of the Church makes itself heard more and more. It points out to Christians the reality of the Mystical Body and the People of God. It calls us to the life of love. It invites everybody to a life of action which, couched in contemplation, is a witness and presence among others. Monastic walls are becoming thinner and the ceilings ever lower. The laity are becoming conscious of their mission and are searching for a genuine spirituality. It is truly the dawn of a new world to which it would not seem unworthy to give as an aim “contemplation in the streets” and to offer the means of achieving it.

But there is another basic element of the contemplative life, above all as it is lived in the world: poverty. Poverty is not a question of having or not having money. Poverty is not material. It is a beatitude.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit.”

It is a way of being, thinking and loving. It is a gift of the Spirit. Poverty is detachment, and freedom and, above all, truth.

Unrestrained by fashion

Go into almost any middle-class home, even a Christian one, and you will see the lack of this beatitude of poverty. The furniture, the drapes, the whole atmosphere are stereotyped, determined by fashion and luxury, not by necessity and truth. This lack of liberty, or rather this slavery to fashion, is one of the idols which attracts a great number of Christians. How much money is sacrificed upon its altar!—without taking into account that so much good could otherwise be done with it. Being poor in spirit means, above all, being unrestrained by what is called fashion; it means freedom. I don’t buy a blanket because it is fashion. I buy it because I need it. Without a blanket my child shivers in bed. Bread, a blanket, a table, fire, are things necessary in themselves. To use them is to carry out God’s plan. “All the rest comes from the evil one,” to paraphrase an expression of Jesus’ about truth.

And this “rest” is fashion, habit, luxury, overindulgence, greed—slavery to the world. One seeks not what is true, but what is pleasing to others. We seem to need this mask. We seem incapable of living without it.

Things get really serious when “styles” come into the picture and prices become astronomical. “This is a Louis XIV—this is genuine crystal—this is etc., etc.” It is more serious still when “styles” enter the homes of churchmen, called by God to preach the Gospel to the poor.

There was a period during which churchly opulence might possibly have been justified. From the Renaissance to the eighteenth century, the triumphant posture of the Church and the need felt by the masses to give worthy honor to God and the things of God, were expressed with extraordinary luxury and pomp. The poor then were not scandalized; indeed they seemed pleased with all that glitter and magnificence. Even more recently I remember my mother who, although poor, spoke with “Christian” pride and satisfaction of the beauty of the bishop’s house, and the length of the prelate’s car parked under the window. But things have changed. If that same bishop today knew of, or rather heard, the curses hurled at his long, elegant car, he would quickly change it for an economy model or better still, he’d use a bicycle.

We speak increasingly of the Church of the Poor, and I don’t think it’s a merely rhetorical phrase. It’s necessary, however, to understand the meaning of the words. When one speaks of poverty in the Church one must not identify it with the beatitude of poverty. This, the beatitude, is an interior virtue, and I cannot, and must not judge my brother by it. Even the wealthy person, or the pontiff covered with a golden cope, can and must possess the beatitude of poverty. Nobody can judge another in this respect. But when one speaks of poverty in the Church, one means social poverty, care for the poor, help for the poor, preaching the Gospel to the poor.

When one speaks of poverty in the Church, one means the kind of life Christians live, and this it is which scandalizes the poor, as Paul was scandalized by the behavior of the Christians of Corinth. The point is, when you hold these meetings, it is not the Lord’s Supper that you are eating, since when the time comes to eat, everyone is in such a hurry to start his own supper that one person goes hungry while another is getting drunk.

Surely you have homes for eating and drinking in? Surely you have enough respect for the community of God not to make poor people embarrassed? (1 Cor. 11 : 20-22) And don’t we perhaps put the poor man to shame when we pass by with our power and riches while he cannot afford to pay the rent?

How can we preach the Gospel to him, while enjoying economic security when he doesn’t know whether tomorrow he will have work and bread? But poverty as a beatitude is not only truth, freedom and justice. It is and always will be love, and its limits become infinite, as infinite as the love of God. Poverty is love for the poor Jesus, and voluntary self-denial.

Jesus could have been rich. He did not have to live the kind of life he lived. No, he wanted to be poor in order to share the restrictions of real poverty, to put up with the lack of comfort, to suffer in his body the hard reality which weighs down the man searching for bread, to experience the abiding instability of one who possesses nothing. This authentic poverty, borne for the sake of love, is the true beatitude of which the Gospel speaks.

It is easy to speak of spiritual poverty, to fill one’s mouth with pious words, and yet not lack anything, not really feel the pinch, have a secure house, a well-stocked larder and the security of a bank account. Let us not deceive ourselves and let us not dilute the most precious things Jesus said. Poverty is poverty and always will be poverty; and it is not enough to make a vow of poverty in order to be “poor in spirit.”

Today the poor are a real cause for scandal; to be rid of this scandal it would be better to spend less time arguing about the nature of chastity and put more emphasis on this beatitude which is in danger of being forgotten by those who are trying to “live as Christians.” If it is true, as it is, that the perfection of the law is love, then it must fully control my desire for possessions and riches. Otherwise I shall not know what the beatitude really means. If I love, if I really love, how can I tolerate the fact that a third of humanity is menaced with starvation while I enjoy the security of economic stability? If I act in that way I shall perhaps be a good Christian, but I shall certainly not be a saint; and today there are far too many good Christians when the world needs saints.

We must learn to accept instability, put ourselves every now and then in the condition of having to say, “Give us this day our daily bread,” with real anxiety because the larder is empty; have the courage, for love of God and one’s neighbor, to give until it hurts and, above all, keep open in the wall of the soul the great window of living faith in the Providence of an all-powerful God.

It is much more serious than it may appear today to well-intentioned Christians, and it sows destruction primarily because we underestimate its danger. Riches are a slow poison, which strikes almost imperceptibly, paralyzing the soul at the moment when it seems healthiest. They are thorns which grow with the grain and suffocate it right at the moment when the corn is beginning to shoot up.

What a number of men and women, religious people, let themselves get caught up in their later lives by the spirit of middle-class tastes. Now that solitude and prayer have helped me to see things more clearly, I understand why contemplation and poverty are inseparable. It is impossible to have a deep relationship with Jesus in Bethlehem, with Jesus in exile, with Jesus the workman of Nazareth, with Jesus the apostle who has nowhere to lay his head, with the crucified Jesus, without having achieved within ourselves that detachment from things, proclaimed with such authority and lived by him.

One will not reach this high state of poverty at once. Indeed, life itself will not be long enough to achieve it fully. But we must think about it, reflect and, above all, pray. Jesus, God of the impossible, will help us. He will work, if need be, the miracle of making the parable of the camel pass though the narrow rusty eye of our poor sick soul.”

—From Letters From the Desert by Carlo Carretto, Orbis Books

(1) La Trappe refers to both a Trappist monastery in France and a brand of Trappist beers brewed by De Koningshoeven Brewery in the Netherlands. The beers are known for their quality and traditional brewing methods. Wikipedia

(*) Religious life

Wikipedia: “On 8 December 1954, he left for the novitiate of El Abiodh, near Oran, Algeria. He later made vows and was ordained a priest. For ten years, he lived an eremitical life in the Sahara composed of prayer, silence and work, an experience he expressed in Letters from the Desert, as in all the books he would later write. It inspired him to create a quiet place in Italy for prayer.

He returned to Italy in 1965 and settled in Spello, Umbria, where Leonello managed to have the fraternity of the Little Brothers of the Gospel entrust the former Franciscan convent of San Girolamo, near the cemetery. Brother Carlo was enthusiastic about the new arrangement. Leonello Radi said: “the main activity of Carlo Carretto was the eight hours of prayer a day, I carried him I do not know how many times with my red Beetle, during the trip we talked and, above all, we prayed”. Soon the spirit of initiative of Carretto and the prestige it enjoys opened the community to the reception of those who, believers or not, wished to spend a period of reflection and search for faith lived in prayer, in manual work and in the exchange of experiences. At the convent where the Fraternity was, many country houses scattered on Mount Subasio were added, transformed into hermitages named after various holy figures. For over twenty years, Carretto was the animator of this center flanked by its many collaborators, friends and benefactors, including the Roman engineer Renato Di Tillo who was very important for the activity of the group and a fraternal friend also of Saint Teresa of Calcutta.