“In 1140, with the Crusaders still ruling Jerusalem, the Spanish philosopher and poet Yehudah Halevi wrote in his Kuzari, or Book of Refutation and Proof in Support of the Despised Religion, that Jews could be closest to the God of Israel within Israel itself. He himself then set out for the land, only to be killed in Jerusalem the following year, run down by an enraged Arab Muslim’s horse as he sang his famous elegy, “Zion ha-lo Tish’ali.”

Yet still some Jews remained in the Holy Land, and Jews continued to emigrate to it, including another renowned philosopher, Maimonides, in the thirteenth century. But the Jews in the Holy Land always faced hardship. At the end of the fifteenth century, the Czech traveler Martin Kabátnik encountered Jews during a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and reported that they still thought of the area as their land:

“The heathens [that is, the Muslim rulers] oppress them at their pleasure. They know that the Jews think and say that this is the Holy Land that was promised to them. Those of them who live here are regarded as holy by the other Jews, for in spite of all the tribulations and the agonies that they suffer at the hands of the heathen, they refuse to leave the place.”15 Shortly thereafter, nearly thirty Jewish communities were counted in Palestine.16

These communities faced continual oppression. In 1576, the Ottoman Sultan Murad III ordered the deportation of one thousand Jews from the city of Safed to Cyprus, not as punishment for anything they had done but arbitrarily, because he wanted to bolster the Cypriot economy.17 It is not known whether the order was carried out, but if it was, the deportees may have been better off, at least in material terms: two travelers who visited Safed in the early seventeenth century said that for the Jews of that city, “life here is the poorest and most miserable that one can imagine…. They pay for the very air they breathe.”18 But they were still there, and they remained.

The Turks taxed the Jews on the basis of the Qur’anic command that the “People of the Book” (primarily Jews and Christians) must be made to “pay the jizya [tax] with willing submission and feel themselves subdued” (9:29). In 1674, a Jesuit priest, Father Michael Naud, wrote that the Jews of Jerusalem were resigned to “paying heavily to the Turk for their right to stay here…. They prefer being prisoners in Jerusalem to enjoying the freedom they could acquire elsewhere…. The love of the Jews for the Holy Land, which they lost through their betrayal [of Christ], is unbelievable.”19 And Jews were coming from elsewhere to live there: “Many of them come from Europe to find a little comfort, though the yoke is heavy.”20 It was indeed.

Even aside from the political oppression, the land itself was increasingly inhospitable. By the end of the eighteenth century, only two hundred fifty thousand to three hundred thousand people, including ten thousand to fifteen thousand Jews, lived in what had become a backwater with a harsh and forbidding terrain and climate.21 Yet still Jews came.

In 1810, the disciples of the great Talmudic scholar known as the Vilna Gaon arrived in the land of Israel from the Russian Empire, and rejoiced even though they were well aware of the hardness of the land to which they had come: Truly, how marvelous it is to live in the good country. Truly, how wonderful it is to love our country…. Even in her ruin there is none to compare with her, even in her desolation she is unequaled, in her silence there is none like her. Good are her ashes and her stones.22 In 1847, the U.S. Navy commander William F. Lynch made an expedition to the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the surrounding areas, and encountered Jews all over the region.

In Tiberias, wrote Lynch, “we had letters to the chief rabbi of the Jews, who came to meet us, and escorted us through a labyrinth of streets to the house of Heim Weisman, a brother Israelite.”23 He found that the Jews of the city “have two synagogues, the Sephardim and Askeniazim, but lived harmoniously together.” He found evidence of continued Jewish immigration: “There are many Polish Jews, with light complexions, among them. They describe themselves as very poor, and maintained by the charitable contributions of Jews abroad, mostly in Europe.”24 In Tiberias, the Jews outnumbered others: “There are about three hundred families, or one thousand Jews, in this town. The sanhedrim consists of seventy rabbis, of whom thirty are natives and forty Franks, mostly from Poland, with a few from Spain. The rabbis stated that controversial matters of discipline among Jews, all over the world, are referred to this sanhedrim. Besides the Jews, there are in Tiberias from three to four hundred Muslims and two or three Latins, from Nazareth.”25 Lynch saw Ottoman oppression up close and held a dim view of the sultanate, of which he wrote presciently: “It needs but the destruction of that power which, for so many centuries, has rested like an incubus upon the eastern world, to ensure the restoration of the Jews to Palestine.”

Palestinians in Palestine? So the Jews were always in the land they supposedly returned to only after two thousand years of absence as a result of the Zionist project. But the Palestinian Arabs were always there also, no? No. Instead, travelers to the area over many centuries agree: the land was desolate and largely depopulated. Writing some seventy years after the Romans expelled the Jews from their land in the year 134, the Roman historian Dio Cassius states: “The whole of Judea became desert, as indeed had been foretold in their sacred rites, fell of its own accord into fragments, and wolves and hyenas, many in number, roamed howling through their cities.”27 An English visitor to Jerusalem wrote in 1590 (spelling as in the original):

“Nothing there is to be scene but a little of the old walls, which is yet Remayning and all the rest is grasse, mosse and Weedes much like to a piece of Rank or moist Grounde.”28 In 1697, the English traveler Henry Maundrell found Nazareth to be “an inconsiderable village,” while Acre was “a few poor cottages” and Jericho a “poor nasty village.” All in all, there was “nothing here but a vast and spacious ruin.”29 Some fifty years later, another English traveler, Thomas Shaw, noted that Palestine was “lacking in people to till its fertile soil.”30 The French count Constantine François Volney, an eighteenth-century historian, called Palestine “ruined” and “desolate,” observing that “many parts” had “lost almost all their peasantry.”31 Volney complained that this desolation was unexpected, for the Ottoman imperial records listed larger populations, which led to tax collection efforts’ being frustrated. Of one area, Volney wrote:

“Upwards of three thousand two hundred villages were reckoned, but, at present, the collector can scarcely find four hundred. Such of our merchants as have resided there twenty years have themselves seen the greater part of the environs…become depopulated. The traveller meets with nothing but houses in ruins, cisterns rendered useless, and fields abandoned. Those who cultivated them have fled.”32 Another English traveler, James Silk Buckingham, visited Jaffa in 1816 and wrote that it had “all the appearances of a poor village, and every part of it that we saw was of corresponding meanness.”33 In Ramle, said Buckingham, “as throughout the greater part of Palestine, the ruined portion seemed more extensive than that which was inhabited.”34 Twenty-two years later, the British nobleman Alexander William Crawford Lindsay, Lord Lindsay, declared that “all Judea, except the hills of Hebron and the vales immediately about Jerusalem, is desolate and barren.”35

In 1840, another traveler to Palestine praised the Syrians as a “fine spirited race of men,” but whose “population is on the decline.” He noted that the land between Hebron and Bethlehem was “now abandoned and desolate,” marked by “dilapidated towns.”36 Jerusalem was nothing more than “a large number of houses…in a dilapidated and ruinous state,” with “the masses…without any regular employment.”37 In 1847, the U.S. Navy’s Lynch noted: “The population of Jaffa is now about 13,000, viz: Turks, 8000; Greeks, 2000; Armenians, 2000; Maronites, 700; and Jews, about 300.”38

Significantly, he counted no Arabs there at all. Still another traveling English clergyman, Henry Burgess Whitaker Churton, saw the desolation of Judea as the fulfillment of Biblical prophecy. In 1852, he published Thoughts on the Land of the Morning: A Record of Two Visits to Palestine. “Soon after leaving the Mount of Olives,” Churton recounted, “the country becomes an entire desolation for eighteen miles of mountain, until we reached the plain of the Jordan. It is foretold (Ezekiel, vi. 14), and is remarkably fulfilled, that Judea should be more desolate than the desert itself. That plain itself is now, in great measure, bare as a desert…”39

The following year, one of Churton’s fellow clergymen, the Reverend Arthur G. H. Hollingsworth, published his own treatise, Remarks Upon the Present Condition and Future Prospects of the Jews in Palestine. Hollingsworth’s observations are jarring to those who have uncritically accepted the idea that Palestine was always considered Arab land before the Jews arrived. According to Hollingsworth, the Arabs had no special affection for the land, and it was the Turks who claimed it: The population of Palestine is composed of Arabs, who roam about the plains, or lurk in the mountain fastnesses as robbers and strangers, having no settled home, and without any fixed attachment to the land.

Hollingsworth found the Christians of the area to be little better off: In many of the ruined cities and villages there exists also, a limited number of Christian families, uncivilized, and not knowing from what race they derive their origin. Poor, and without influence, they tremblingly hold their miserable possessions from year to year, without security, and without wealth, in a land which they confess is not their own. The Turks monopolize for themselves the spoils and power of conquerors. They claim the land, they levy the uncertain and oppressive taxes.40

Even the Ottoman government, however, was not at home there:

“No Christian is secure against insult, robbery, and ruin. The Ottoman government is weak and violent, rapacious and uncertain in its justice, tyrannical and capricious; their soldiery and merchants amount to a few thousands, in a country where millions were formerly happy and prosperous. The influence of such a government never extends beyond the shadow of their standards. They are always in the attitude of a hostile army, encamped in a land which is only held by forcible possession; like a garrison under arms, they retain the country by the law of the sword and not by inheritance. It is a sullen conquest and not a peaceable settlement.41

Hollingsworth, like so many others, bore witness to the land’s steady depopulation:

The Arab and Christian populations diminish every year. Poverty, distress, insecurity, robbery, and disease continue to weaken the inhabitants of this fine country.42 He did notice, however, one group that was increasing in number: Amongst the scattered and feeble population of this once happy country, is found, however, an increasing number of poor Jews; some of their most learned men reside in the holy cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, and Tiberias. Their synagogues are still in existence. Jews frequently arrive in Palestine from every nation in Europe, and remain there for many years; and others die with the satisfaction of mingling their remains with their forefathers’ dust, which fills every valley, and is found in every cave.43

The Jews weren’t exactly thriving in Palestine. They eked out an existence there against enormous odds. Hollingsworth explains that the Turks made life extremely difficult for the Jews: He creeps along that soil, where his forefathers proudly strode in the fulness of a wonderful prosperity, as an alien, an outcast, a creature less than a dog, and below the oppressed Christian beggar in his own ancestral plains and cities. No harvest ripens for his hand, for he cannot tell whether he will be permitted to gather it. Land occupied by a Jew is exposed to robbery and waste. A most peevish jealousy exists against the landed prosperity, or commercial wealth, or trading advancement of the Jew. Hindrances exist to the settlement of a British Christian in that country, but a thousand petty obstructions are created to prevent the establishment of a Jew on waste land, or to the purchase and rental of land by a Jew…. What security exists, that a Jewish emigrant settling in Palestine, could receive a fair remuneration for his capital and labour? None whatever. He might toil, but his harvests would be reaped by others; the Arab robber can rush in and carry off his flocks and herds. If he appeals for redress to the nearest Pasha, the taint of his Jewish blood fills the air, and darkens the brows of his oppressors; if he turns to his neighbour Christian, he encounters prejudice and spite; if he claims a Turkish guard, he is insolently repulsed and scorned. How can he bring his capital into such a country, when that fugitive possession flies from places where the sword is drawn to snatch it from the owner’s hands and not protect it?44

By 1857, according to the British consul in Palestine, “the country is in a considerable degree empty of inhabitants and therefore its greatest need is that of a body of population.”45

Henry Baker Tristram, yet another in the seemingly endless stream of English travelers, reported in the 1860s that “the north and south [of the Sharon plain] land is going out of cultivation and whole villages are rapidly disappearing from the face of the earth. Since the year 1838, no less than 20 villages there have been thus erased from the map and the stationary population extirpated.”46

The most celebrated chronicler of Palestine’s pre-Zionist desolation was Mark Twain, who wrote about his travels in the Holy Land in The Innocents Abroad in 1869. It is Twain’s literary genius that gives us the most indelible images of the wasteland that was Palestine:

“Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies. Where Sodom and Gomorrah reared their domes and towers, that solemn sea now floods the plain, in whose bitter waters no living thing exists—over whose waveless surface the blistering air hangs motionless and dead—about whose borders nothing grows but weeds, and scattering tufts of cane, and that treacherous fruit that promises refreshment to parching lips, but turns to ashes at the touch. Nazareth is forlorn; about that ford of Jordan where the hosts of Israel entered the Promised Land with songs of rejoicing, one finds only a squalid camp of fantastic Bedouins of the desert; Jericho the accursed, lies a moldering ruin, to-day, even as Joshua’s miracle left it more than three thousand years ago; Bethlehem and Bethany, in their poverty and their humiliation, have nothing about them now to remind one that they once knew the high honor of the Saviour’s presence; the hallowed spot where the shepherds watched their flocks by night, and where the angels sang Peace on earth, good will to men, is untenanted by any living creature, and unblessed by any feature that is pleasant to the eye.

“Renowned Jerusalem itself, the stateliest name in history, has lost all its ancient grandeur, and is become a pauper village; the riches of Solomon are no longer there to compel the admiration of visiting Oriental queens; the wonderful temple which was the pride and the glory of Israel, is gone, and the Ottoman crescent is lifted above the spot where, on that most memorable day in the annals of the world, they reared the Holy Cross. The noted Sea of Galilee, where Roman fleets once rode at anchor and the disciples of the Saviour sailed in their ships, was long ago deserted by the devotees of war and commerce, and its borders are a silent wilderness; Capernaum is a shapeless ruin; Magdala is the home of beggared Arabs; Bethsaida and Chorazin have vanished from the earth, and the “desert places” round about them where thousands of men once listened to the Saviour’s voice and ate the miraculous bread, sleep in the hush of a solitude that is inhabited only by birds of prey and skulking foxes.

“Palestine is desolate and unlovely. And why should it be otherwise? Can the curse of the Deity beautify a land? Palestine is no more of this work-day world. It is sacred to poetry and tradition—it is dream-land.47

In Jezreel, Twain recounted the Bible’s Song of Deborah and Barak, and then added:

“Stirring scenes like these occur in this valley no more. There is not a solitary village throughout its whole extent—not for thirty miles in either direction. There are two or three small clusters of Bedouin tents, but not a single permanent habitation. One may ride ten miles, hereabouts, and not see ten human beings.”48

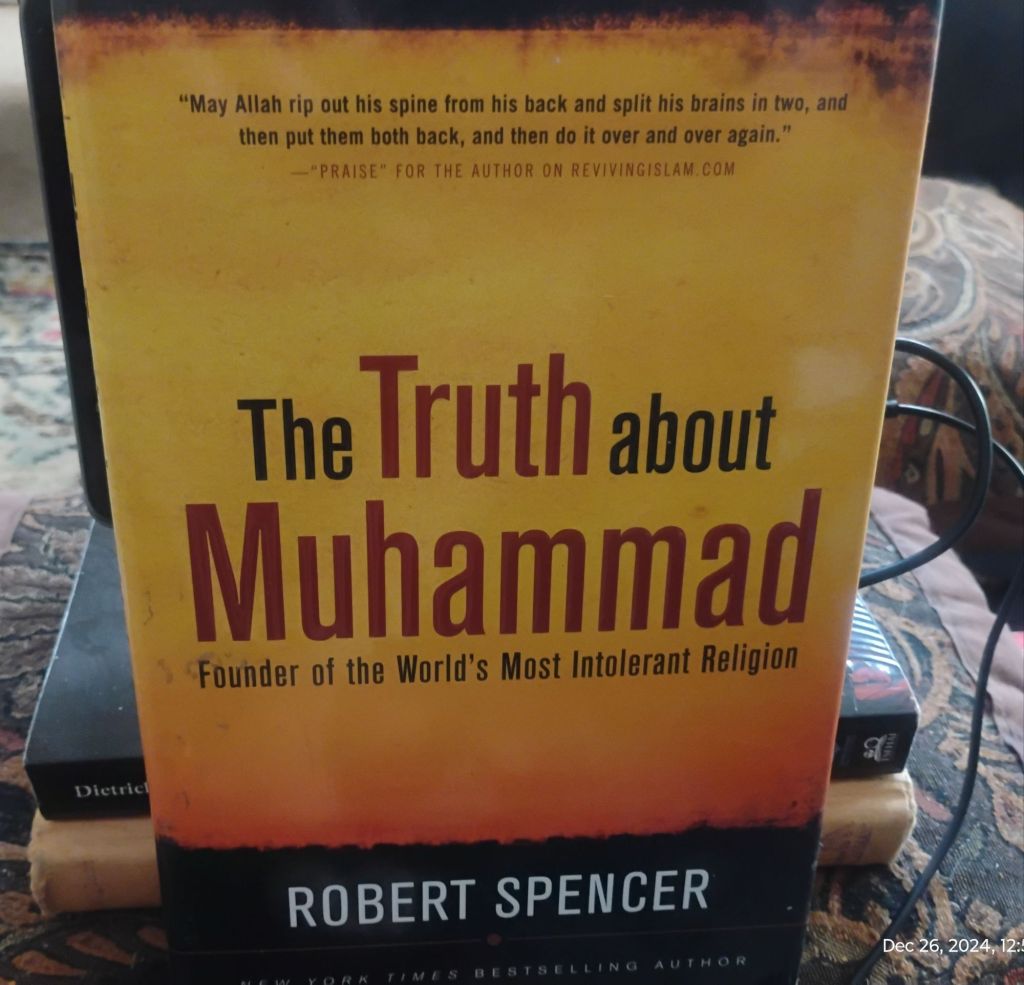

— from The Palestinian Delusion by Robert Spencer, footnotes provided in text.