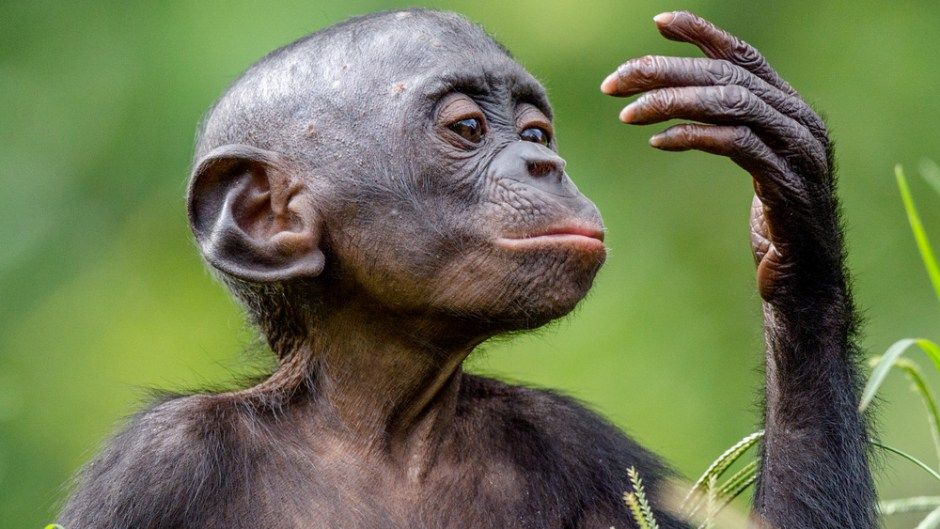

“The Russian intelligentsia produced a faith based upon a strange syllogism:

‘Man is descended from the apes, therefore we must love one another.’” — Vladimir Solovyev.

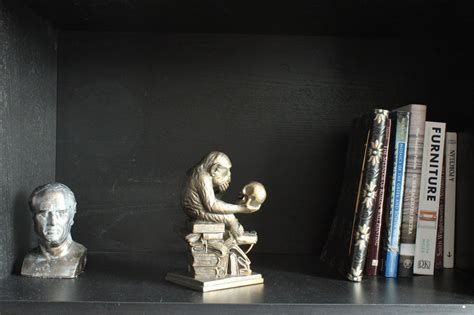

On Lenin’s desk in the Kremlin there stood, for most of the years he worked there, a strange bronze statue of an ape gazing with an expression of profound bewilderment and dismay at an oversize human skull. It stood about ten inches high, and occupied a dominating position on the desk behind the inkwell. The ape was sitting, or rather squatting, on a heap of books in a posture which is a grotesque parody of Rodin’s Le Penseur. There is nothing in the least amusing about the appearance of the ape, which is sordidly bestial, with its small head and great curving shoulders and long dangling arms; and the human skull, with gaping mouth and empty eye sockets, is even less amusing. The ape gazes ponderously at the skull, and the skull gazes back at the ape. We can only guess at the nature of the interminable dialogue which is being maintained between them

Lenin made no secret of his affection for the ape, which was displayed in such a prominent position for all to see. It was the only piece of sculpture on the desk, the first thing that met the eye; and whenever Lenin looked up from his desk to gaze at the very large photograph of Karl Marx and the plaque bearing the name of Stepan Khalturin in gold letters, he would inevitably see the ape. There is a sense in which its vivid presence dominated the room.

Long after Lenin’s death, when his study in the Kremlin was converted into a museum and when all the objects originally on the desk — the telephone, the scissors, the paper knives, the cigarette lighter he used for burning papers — were placed in the exact positions they had occupied in his lifetime, then the ape was not forgotten. This, too, was placed in its proper position, and so it appears, usually half hidden but nevertheless clearly discernible, in the photographs taken of the study. His devout followers were concerned to maintain the room exactly as he left it. Not even the ape must be removed.

This ugly and vulgar statue was not designed especially for Lenin. It was mass-produced toward the end of the nineteenth century. As a dubious ornament or conversation piece, it could be seen in countless homes in France, Germany, Scandinavia and Russia, where it appealed to bourgeois taste, its very ugliness and vulgarity contributing to its popularity. It represented, if it represented anything at all, a mocking commentary on the Darwinian theory and showed the ape, having long outlived the human race, interrogating in its bemused fashion the existence of man.

Lenin was one of those men who knew exactly what he liked and disliked. There was no object in the room which did not have a precise meaning for him. There was, for example, a strip of felt on the floor under his desk, to prevent his feet from becoming chilled in winter. His secretaries decided to replace it with a white bearskin rug. Immediately there was an uproar. He wanted to know why he was expected to live in capitalist comfort, and who exactly was responsible for this attempt to smother him in luxury. His secretaries pointed out gently that even minor officials permitted themselves the luxury of a small bearskin rug, but he was never completely reconciled to its presence: it did not fit into the orderly image he had conceived for the room in which he spent most of the day.

Then there was the tall potted palm with glossy green leaves which stood near the window. This, too, had a special and intricate meaning for him. Every day he would wash down the leaves, examining them to see that no blight had touched them. It was the only other living thing in the room, and for some reason he wanted it to flourish. He could not stand having cut flowers in the room; he hated the dropping of the petals, the visible evidence of decay. The palm however was permanent; it resisted decay, and was always glossy. People were puzzled that he paid so much attention to the palm, but there was a very simple explanation. In Simbirsk and Kazan, and later in Moscow and St. Petersburg, his mother had always possessed a collection of potted plants, and as a child and as a young man it was one of his duties to wash down the leaves. The potted palm was therefore not an irrelevant decoration in an otherwise utilitarian office. The palm was the outward and visible sign of his affection and attachment to his family.

Since all the other objects in the room had a definite meaning for him, it is necessary to discover the meaning he attached to the ape, which occupied such a commanding position in the room. In just such a position a deeply religious man would have placed a crucifix, a statue of Buddha, or some other symbol representing his faith. Lenin placed an ape. Why?

The explanation would seem to lie in the idolatrous attitute of the nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia toward science. An absurd autocratic state had come into existence, which completely failed to answer the needs of the people. It was transparently out of date, inefficient, corrupt, and sterile. Men turned their backs on the state and the Orthodox Church, which was also becoming increasingly remote from the people, and pinned their faith on science. Science alone provided the key to the future. For a Russian intellectual to dispute Darwinism or any other acceptable scientific theory was to commit a heresy. Science, however mechanical, however dangerous and arbitrary, was itself an article of faith. When the great philosopher Vladimir Solovyev wrote,

“The Russian intelligentsia produced a faith based upon a strange syllogism: man is descended from the apes, therefore we must love one another,” he was saying in effect that the Russian intelligentsia firmly believed that science would produce the reign of love among men; and Lenin, who never tired of insisting against all the evidence that Marxism was purely scientific in character, firmly believed that once the Marxist state had been established, then and only then would men be able to live together in peace and concord.

But it is in the nature of science to be inhuman. It cannot legislate for men in their infinite variety; it can only legislate for them as statistics, as trends, or as obstacles to the carrying out of scientific laws. Lenin was perfectly prepared to regard men as statistics or as trends; he was equally prepared to regard them as obstacles standing in the path of his scientific dictatorship, and he had no compunction in destroying whole classes in order to vindicate the laws of science. The aristocracy, the bourgeois, the peasantry, and the Orthodox priests, all these must be destroyed in order that the dictatorship of the proletariat might be established. It was a breathtaking enterprise, for it meant destroying or forcing into new molds considerably more than nine tenths of the population of Russia.

In spite of the fact that the enterprise was essentially absurd, and the scientific theories lacked any basis in science, he persisted in it. Inevitably he came to regard men simply as statistics, as ciphers, to be moved about according to his will. It was not that he despised men or wanted to humiliate them in any way — one cannot despise or humiliate statistics — it was simply that they no longer had any existence for him, as men. They were figures printed on a page, having no existence outside the page. They were nullities, possessing only the value which he chose to place on them. There was nothing to prevent him tearing out whole pages of statistics, to make the book smaller, more compact and more manageable.

The character that emerges from his actions and his writings is that of the pure nihilist, utterly remote from normal human preoccupations, possessed of an unyielding belief in the validity of science, adept in all the arts of destruction. Like Nechayev, he was dedicated to “terrible, total, merciless and universal destruction”. He was a man whose conviction of the worthlessness of existence was such that he could make life interesting for himself only by projecting his personality on a thousand years of history. He was utterly without fear, because nothing mattered to him except that the laws of his pretended science should be vindicated, whatever the cost in life or suffering. He demanded absolute loyalty, yet he himself had no loyalty to any individual, not even to his most devoted followers, whom he could discard without a pang, or manipulate as though they too were a portion of the statistics of power. His temperament was aristocratic, remote, ironical, faintly contemptuous. In the end all Russia had to become his private estate, which he ruled from the Kremlin and his palatial house at Gorki. (All Emphasis added throughout — SH)

In the light of Lenin’s character and beliefs, the ape and the skull acquire a terrible significance. They are the emblems of the nullity and degradation of the human spirit. They represent the anarchic forces on which he was determined to impose scientific order: all men are apes, and they must move about at his bidding, or else they will become skulls. They must be trained and herded into schools, to receive the instructions of the schoolmaster. They must not dispute with him or with any of his successors, for freedom to dispute is not granted to them. He demands mindless obedience because, being apes, they are mindless and deserve no better fate.

Lenin had many sins, but the gravest was a supreme contempt for the human race. Like Marx he possessed an overwhelming contempt for the peasants. In a famous passage Marx spoke of “the idiocy of rural life” and described the peasantry of France as nothing more than a lifeless sack of potatoes which could never be stirred into activity: it was like a corpse thrown down to rot. But Lenin went beyond Marx. Not only the peasants, but all classes of society were anathema to him — except the proletariat, with which he had almost no contact. He surrounded himself with intellectuals and theoreticians, and he despised them as much as he despised the peasants, for he never found one who was his intellectual equal. His tragedy was that he was never able to sharpen his mind against one morally and intellectually more powerful than his own. The little men clustered at his heels. Zinoviev, Radek, Kamenev, Bukharin, and all the rest fade into shadows beside him. They, too, were his servants, who aped their master without possessing either his intellectual acumen or his remorseless power to carry his theories to their logical conclusion.

Those conclusions were among the hardest which have been visited on the human race. They involved slavery to a theory which demanded the absolute submission of the individual to the brooding genius of the state, the Grand Inquisitor, the relentless power which alone possesses the key to the mystery. So in The Brothers Karamazov Dostoyevsky puts into the mouth of the Grand Inquisitor as he addresses Christ, the words: “We shall convince them that they can never be free until they renounce their freedom in our favor and submit wholly to us, and they will all be happy, all the millions, except the hundred thousand who rule over them. We have corrected your great work, and we have based it on Miracle, Mystery and Authority.” But the Grand Inquisitor was not appealing to the Miracle, Mystery and Authority of Christ; he was appealing to his own theory that men deserved only to be enslaved.

Lenin was the great simplifier, but there are no simple solutions. He wanted to bring about the ideal state — and there is no doubt about the genuineness of his passion for the ideal state — but the ideal eluded him, as it has eluded everyone else. Toward the end of his life he realized that after the Russian people had suffered and submitted to intolerable sacrifices under his dictatorship, he had led them along the wrong path. “I am, it seems, strongly guilty before the workers of Russia,” he declared; and those words were his genuine epitaph. There are few rulers in history who have uttered so clear a mea culpa.

That Stalin should have been his successor was a fearful irony. That coarse, brutal and paranoid dictator possessed none of Lenin’s intellectual gifts and could scarcely write a sentence which was not a mockery of the Russian language. Under him Communism became a tyranny of such vast proportions that it exceeded all the tyrannies the world had known up to his time. Lenin, with his harsh intellect, his egotism, his phenomenal vigor, his always flawed yet ever impressive achievement, remained oddly human; Stalin was a monster. Yet it is important to observe that there could have been no Stalin without Lenin. Stalin was Lenin’s child; and Lenin, who hated and despised and feared him, must bear sole responsibility for bringing Stalin to power.

Once Lenin had decided that all means were permissible to bring about the dictatorship of the proletariat, with himself ruling in the name of the proletariat, he had committed Russia to intolerable deprivations of human freedom. His power was naked power; his weapon was extermination; his aim the prolongation of his own dictatorship. He would write, “Put Europe to the flames” — and think nothing of it. He could decree the deaths of thousands upon thousands of men, and their deaths were immaterial, because they were only statistics impeding the progress of his theory. The butchery in the cellars of the Lubyanka did not concern him. He captured the Russian Revolution and then betrayed it, and at that moment he made Stalin inevitable.

The lawlessness of Communist rule was of Lenin’s own making. Ordinary human morality never concerned him; from the beginning he was using words like “extermination” and “merciless” as though they were counters in a game. Whatever he decreed was law, and whoever opposed his decree was outside the law, and therfore possessing no rights, not even the right to breathe. Yet he had, on occasions, the intellectual detachment which permitted him to see that some of his decrees were senseless, and with the New Economic Policy he admitted the error of his ways. Stalin, possessing no intellectual detachment, never admitted the error of his ways, and he went on murdering mercilessly and exalting his own cult as though “scientific Marxism” had come into existence for no other purpose than to satisfy his lust for power. Lenin, too, lusted for power, but he had sufficient common humanity to regard the cult that grew up around him with detestation.

“Lenin is not in the least ambitious,” wrote Lunacharsky. “I believe he never looks at himself, never glances in the mirror of history, never even thinks about what posterity will say about him — he simply does his work.” Lunacharsky was writing while Lenin was still alive and before his papers were published; and there is more than enough evidence in his papers to show that from a very early period he regarded himself as a figure of history. He believed, quite simply, that he was ushering in a new age. He had no false modesty. He saw himself as the heroic defender of a new faith and as one come to avenge the injustices and miseries of the past.

We who come after him do not have to take him at his own valuation. The state he brought into being proved to be more unjust and incomparably more tyrannical than the state he overthrew. He announced that everything would be new, but in fact there was nothing new except the names; for all tyrannies are alike, differing only in their degree of tyranny. The Cheka was only the tsarist Okhrana under another name: more unpitying, more terrifying, and effective only when it exterminated opposing groups to the last man. Under Stalin, the Cheka, more murderous than ever, became the real ruler of the country; and one by one its leaders died in the same manner as the victims.

When the rule of a country is given over to the secret police, then by the very nature of things it loses its humanity, places itself outside the frontiers of civilization, and possesses no history; for the repetition of crimes is not history. The government which Lenin introduced, believing it to be new, was as old as man, for there is nothing new about tyranny. Such a government is only “government by the ape and the skull”.

He was one of those who knew that human misery is rooted not in the laws of nature but in those institutions which man must learn to change. So he changed them, and the tragedy was that the change was only superficial. The autocracy remained autocratic, and the continuing public debate, which since the time of Cleisthenes had been the characteristic of a civilized community, was never permitted. The autocrat told the philosophers what to think, the poets what to write, the artists what to paint, and the workmen when and how to work; and all obeyed him, because he had the power to enforce obedience. That the autocrat should then believe that he was conferring benefits on the human race is the final irony.

In The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon Karl Marx explained in a pregnant paragraph what happens when revolutions take place and how they are imprisoned by the dead weight of the past. He said:

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly found, and given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something entirely new, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, battle slogans and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in time-honored disguise and this borrowed language.

So it was with Lenin, who never realized that he was conjuring up the dead spirits of the past when he was sketching those vast plans for the reorganization of every aspect of life in Russia. “We shall destroy everything,” he said, “and on the ruins we shall build our temple.” He destroyed everything he could destroy, and built a new temple which was only the old temple with a new façade. In our own age such temples have become anachronisms. It is not by virtue of savage doctrinaire minds that the world’s purpose will be assured, but by open debate and by gentle persuasion. We no longer need to watch the ape playing with the skull. We have learned that doctrines are poison, and that dictatorship of any kind is an affront to human dignity. We have also learned that the state which becomes a prison camp ultimately includes the rulers within the barbed-wire walls.

For a little while longer the specter of Lenin will continue to haunt the earth, the implacable doctrinaire still ordering millions of people from the grave. Soon he will sink into the shadows to join the ghosts of all the ancient, anachronistic kings and conquerors who proclaimed themselves to be the sole guardians of the truth, the God-given leaders of mankind. He was a man utterly without fear, his spirits rising in adversity, humble and proud by turns, human and inhuman, half Chuvash tribesman and half dry-as-dust German professor dedicated to a theory of destruction, and by one of the strangest accidents of history he conquered Russia and came to dominate the world’s stage. He belongs to the company of Sennacherib, Nebuchadnezzar, Genghis Khan and Tamerlane — and therefore to ancient legend.

How the Revolution Operates:

“Shotman argued that they could hardly take over power while lacking the experts to run the machinery of government.

“Pure absurdity!” Lenin replied. “Any workman can learn to become a minister in a few days. There is no need for any special ability. It is not even necessary that he should understand the technicalities. That side of things will be done by the functionaries who will be compelled to work for us.”