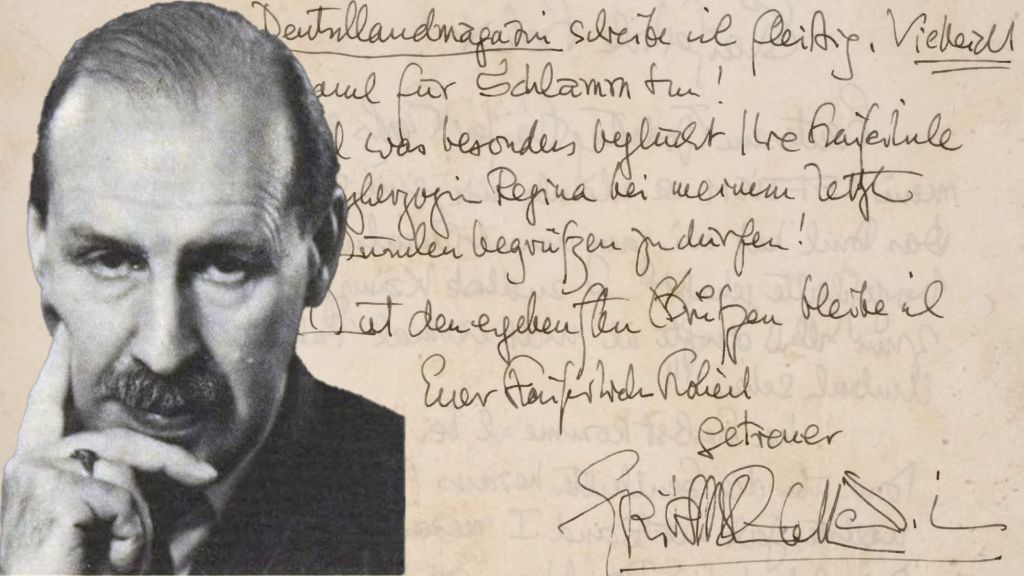

Described as a “Walking Book of Knowledge” by William F. Buckley Jr., Kuehnelt-Leddihn had an encyclopedic knowledge of humanities and was a polyglot, able to speak eight languages and read seventeen others. His early books The Menace of the Herd (1943) and Liberty or Equality (1952) were influential within the American conservative movement. An associate of Buckley Jr., his best-known writings appeared in National Review, where he was a columnist for 35 years.

From Wikipedia and public sources

See “The Smartest Man I Ever Met” by Karl Keating

Amazon excerpt: “Sometime in the 18th century, the word equality gained ground as a political ideal, but the idea was always vague. In this treatise, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn argues that it reduced to one simple and very dangerous idea: equality of political power as embodied in democracy.

He marshals the strongest possible case that democratic equality is the very basis, not of liberty, as is commonly believed, but of the total state. He uses national socialism as his prime example.

He further argues the old notion of government by law is upheld in old monarchies, restrained by a noble elite. Aristocracy, not democracy, gave us liberty. On his side in this argument, he includes the whole of the old liberal tradition, and offers overwhelming evidence for his case.

In our times, war and totalitarianism do indeed sail under the democratic flag. This book, capable of overturning most of what you thought you knew about political systems, was first published in 1952.”

After publishing books like Jesuiten, Spießer und Bolschewiken in 1933 (published in German by Pustet, Salzburg) and The Menace of the Herd in 1943, in which he criticized the National Socialists as well as the Socialists, he remained in the United States, as he could not return to the Austria that had been incorporated into the Third Reich. Kuehnelt-Leddihn moved to Washington, D.C. in 1937, where he taught at Georgetown University. He also lectured at Fordham University, teaching a course in Japanese.[5]

Following the Second World War, he resettled in Lans, where he lived until his death.[6] He was an avid traveler: he had visited over seventy-five countries (including the Soviet Union in 1930–1931), as well as all fifty states in the United States and Puerto Rico.[7][2] In October 1991, he appeared on an episode of Firing Line, where he debated monarchy with Michael Kinsley and William F. Buckley Jr.[8]

Kuehnelt-Leddihn wrote for a variety of publications, including Chronicles, Thought, the Rothbard-Rockwell Report, Catholic World, and the Norwegian business magazine Farmand. He also worked with the Acton Institute, which declared him after his death “a great friend and supporter.”[9] He was an adjunct scholar of the Ludwig von Mises Institute.[10] For much of his life, Kuehnelt was also a painter; he illustrated some of his own books.

Wilsonianism

His socio-political writings dealt with the origins and the philosophical and cultural currents that formed Nazism. He endeavored to explain the intricacies of monarchist concepts and the systems of Europe, cultural movements such as Hussitism and Protestantism, and the disastrous effects of an American policy derived from antimonarchical feelings and ignorance of European culture and history.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn directed some of his most significant critiques towards Wilsonian foreign policy activism. Traces of Wilsonianism could be detected in the foreign policies of Franklin Roosevelt; specifically, the assumption that democracy is the ideal political system in any context. Kuehnelt-Leddihn believed that Americans misunderstood much of Central European culture such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[11] which Kuehnelt-Leddihn claimed as one of the contributing factors to the rise of Nazism. He also highlighted characteristics of the German society and culture (especially the influences of both Protestant and Catholic mentalities) and attempted to explain the sociological undercurrents of Nazism. Thus, he concludes that sound Catholicism, sound Protestantism, or even, probably, sound popular sovereignty (German-Austrian unification in 1919) would have prevented National Socialism although Kuehnelt-Leddihn rather dislikes the latter two.

Nazism

Contrary to the prevailing view that the Nazi Party was a radical right-wing movement with only superficial and minimal leftist elements, Kuehnelt-Leddihn asserted that Nazism (National Socialism) was a strongly leftist, democratic movement ultimately rooted in the French Revolution that unleashed forces of egalitarianism, conformity, materialism and centralization.[12] He argued that Nazism, fascism, radical-liberalism, anarchism, communism and socialism were essentially democratic movements, based upon inciting the masses to revolution and intent upon destroying the old forms of society. Furthermore, Kuehnelt-Leddihn claimed that all democracy is basically totalitarian and that all democracies eventually degenerate into dictatorships. He said that it was not the case for “republics” (the word, for Kuehnelt-Leddihn, has the meaning of what Aristotle calls πολιτεία), such as Switzerland, or the United States, as it was originally intended in its constitution. However, he considered the United States to have been to a certain extent subject to a silent democratic revolution in the late 1820s.

Monarchy

In Liberty or Equality, his masterpiece, Kuehnelt-Leddihn contrasted monarchy with democracy and presented his arguments for the superiority of monarchy: diversity is upheld better in monarchical countries than in democracies. Monarchism is not based on party rule and “fits organically into the ecclesiastic and familistic pattern of Christian society.” After insisting that the demand for liberty is about how to govern and by no means by whom to govern a given country, he draws arguments for his view that monarchical government is genuinely more liberal in this sense, but democracy naturally advocates for equality, even by enforcement, and thus becomes anti-liberal.[13] As modern life becomes increasingly complicated across many different sociopolitical levels, Kuehnelt-Leddihn submits that the Scita (the political, economic, technological, scientific, military, geographical, psychological knowledge of the masses and of their representatives) and the Scienda (the knowledge in these matters that is necessary to reach logical-rational-moral conclusions) are separated by an incessantly and cruelly widening gap and that democratic governments are totally inadequate for such undertakings.

Vietnam

In February 1969, Kuehnelt-Leddihn wrote an article arguing against seeking a peace deal to end the Vietnam War.[14] Instead, he argued that the two options proposed, a reunification scheme and the creation of a coalition Vietnamese government, were unacceptable concessions to the Marxist North Vietnam.[14] Kuehnelt-Leddihn urged the US to continue the war[14] until the Marxists were defeated.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn also denounced the US Bishops’ 1983 pastoral The Challenge of Peace.[15] He wrote that “The Bishops’ letter breathes idealism… moral imperialism, the attempt to inject theology into politics, ought to be avoided except in extreme cases, of which abolition and slavery are examples.”[15]

The complete work and correspondence of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn is available at the Brenner Archive, University of Innsbruck

Kuehnelt-Leddihn was married to Countess Christiane Gräfin von Goess,[16] with whom he had three children.[17] At the time of his death in 1999, he was survived by all four of them, as well as seven grandchildren.[9] He and his wife were buried at their village church in Lans.[5]

“World’s most fascinating man“

Kuehnelt held friendships with many of the major conservative intellectuals and figures of the 20th century, including William F. Buckley Jr., Russell Kirk, Crown Prince Otto von Habsburg, Friedrich A. Hayek, Mel Bradford, Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke, Ernst Jünger, and Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI).[18] According to Buckley, Kuehnelt-Leddihn was “the world’s most fascinating man.”[19] Catholic apologist Karl Keating stated that Kuehnelt-Leddihn was the most intelligent man he ever met.[5]

In 1931, while in Hungary, Kuehnelt-Leddihn stated that he had a supernatural experience. While conversing with a friend, the two men saw Satan appear before them. Kuehnelt-Leddihn recounts this experience as so:

“Slowly, in that moment, to both of us, Satan appeared as Satan appears in primitive books. Naked, reddish, horns, long tongue, trident, and we both exploded laughing. In other words, laughing hysterically. As I later found out, in apparitions of the Devil, this is a natural reaction, that you laugh hysterically.”[20]

Sayings

Welfare State’ is a misnomer, for every state must care for the common good.”[23]

“For the average person, all problems date to World War II; for the more informed, to World War I; for the genuine historian, to the French Revolution.”[24]

“Liberty and equality are in essence contradictory.”[25]

“There is little doubt that the American Congress or the French Chambers have a power over their nations which would rouse the envy of a Louis XIV or a George III, were they alive today. Not only prohibition, but also the income tax declaration, selective service, obligatory schooling, the fingerprinting of blameless citizens, premarital blood tests—none of these totalitarian measures would even the royal absolutism of the seventeenth century have dared to introduce.”[26]

“I am for the word Rightist. Right is right and left is wrong, you see, and in all languages ‘right’ has a positive meaning and ‘left’ a negative one. In Italian, typically, la sinistra is ‘the left’ and il sinistro is ‘the mishap’ or ‘the calamity.’ Japanese describes evil as hidar-imae, ‘the thing in front of the left.’ And in the Bible, it says in Ecclesiastes, which the Hebrews call Koheleth, that “the heart of the wise man beats on his right side and the heart of the fool on his left.'[27]

__________

+ Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn. Liberty or Equality.

+ St. Thomas Aquinas on the ideal form of government

References

Campbell, William F. (18 September 2008). “Erik Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn: A Remembrance”. American Conservative Thought. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von (1986). “Erik Kuehnelt-Leddihn Curriculum Vitae”. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020.

William F., Jr., Buckley (31 December 1985). “A Walking Book of Knowledge”. National Review. p. 104.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von (26 November 1939). “Our Coins Criticized: Visitor Finds Artistic Faults in All Except the Quarter”. The New York Times. p. 75.

Keating, Karl (22 June 2015). “The Smartest Man I Ever Met”. Catholic.com.

Rutler, George W. (19 November 2007). “Erik Von Kuehnelt-Leddihn”. Crisis Magazine. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

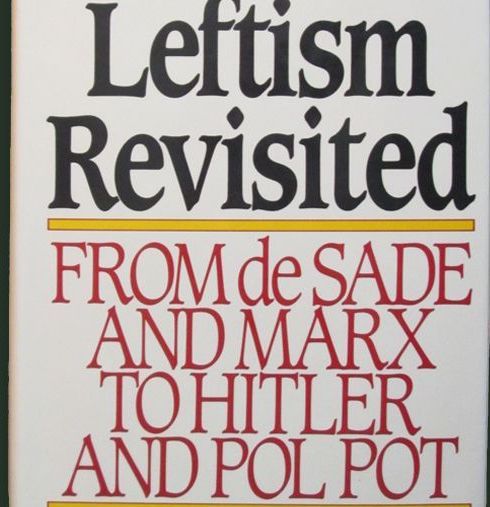

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von. (1990) Leftism Revisited. Back Cover

“Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr.; S0915; The New Europe and the Uses of Monarchy”. American Archive. 28 October 1991.

“Erik Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (1909–1999)”. Acton Institute. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

Rockwell, Lew (31 July 2008). “Remembering Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn”. LewRockwell.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

Baltzersen, Jørn K. (31 July 2009). “The Last Knight of the Habsburg Empire”. LewRockwell.com. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

Congdon, Lee (26 March 2012). “Kuehnelt-Leddihn and American Conservatism”. Crisis Magazine. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

Lukacs, John (1999). “Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn: A Memoir” (PDF). The Intercollegiate Review. Vol. 35, no. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

Von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik (11 February 1969). “No Quick Peace In Vietnam”. National Review.

Kari, Camilla J. (2004). Public Witness: The Pastoral Letters of the American Catholic Bishops. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8146-5833-8. OCLC 260105860.

Member, Acton Staff (9 March 2022). “Erik Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn”. Acton Institute.

St. Mary’s University (San Antonio, Tex ) (5 December 1958). “The Rattler (San Antonio, Tex.), Vol. 41, No. 7, Ed. 1 Friday, December 5, 1958”. The Portal to Texas History.

Adamo, F. Cooper (November 2021). “Remembering Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn”. Chronicles Magazine.

“Erik Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn”. Religion & Liberty. Vol. 9, no. 5. 1 September 1999. p. 3.

Klinghoffer, David (7 December 2020). “When Erik Saw the Devil”. National Review. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020.

Brownfeld, Allan C. (1 July 1974). “Leftism, by Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn”. The Freeman.

Chamberlain, John (1 July 1991). “Leftism Revisited”. The Freeman. Vol. 41, no. 7.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von (1969). The Timeless Christian. Franciscan Herald Press. p. 211.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von (1990). Leftism Revisited: From de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Pol Pot. Regenery Gateway. p. 319.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Erik von (2014). Liberty or Equality: The Challenge of Our Time. The Mises Institute. p. 3.

Liberty or Equality: The Challenge of Our Time. p. 10.

“Christianity, the Foundation and Conservator of Freedom”. Religion & Liberty: Volume 7, Number 6. 20 July 2010.