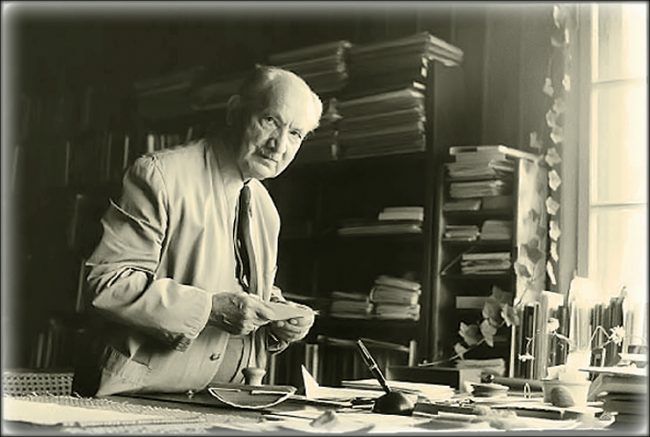

There is scarcely a Catholic philospher (of the Left especially) who does not consider the Catholic apostate Martin Heidegger a brilliant philospher whose teachings in no small way show us the way out of the restraints of biblical literalism and philosophical realism (in other words, the Christian revelation of God in Christ Jesus, the Incarnation), which they find suffocating. But Heidegger’s philosophy was for him far more than merely academic as his life choices, which he considered perfectly consonant with his substantial body of work, show. SH.

Heidegger in Ruins

“Martin Heidegger’s sympathies for the conservative revolution and National Socialism have long been well known. As the rector of the University of Freiburg in the early 1930s, he worked hard to reshape the university in accordance with National Socialist policies.

He also engaged in an all-out struggle to become the movement’s philosophical preceptor, “to lead the leader.” Yet for years, Heidegger’s defenders have tried to separate his political beliefs from his philosophical doctrines. They argued, in effect, that he was good at philosophy but bad at politics. But with the 2014 publication of Heidegger’s Black Notebooks, it has become clear that he embraced a far more radical vision of the conservative revolution than previously suspected. His dissatisfaction with National Socialism, it turns out, was mainly that it did not go far enough.

The notebooks show that far from being separated from Nazism, Heidegger’s philosophy was suffused with it. In this book Richard Wolin explores what the notebooks mean for our understanding of arguably the most important philosopher of the twentieth century, and of his ideas—and why his legacy remains radically compromised.

Heidegger’s correspondence is intellectually significant for several reasons. For one, it is widely acknowledged that, as Heidegger was a philosopher of Existenz, many of his fundamental philosophical impulses derived from his own life experiences: his “conversion” to Protestantism circa 1917, the Kriegerlebnis (war experience) of World War I—the defining event of Heidegger’s “Generation”—the collapse of the Weimar Republic, and the rise of National Socialism.

Heidegger’s letters offer invaluable testimony concerning the ways that these transformative existential episodes impacted his Denken. As Heidegger avowed in a letter to Karl Löwith of 19 August 1921: “I work in a concrete factical manner, from out of my ‘I am’—from out of my spiritual, factical heritage/milieu/life context, from out of that which becomes accessible to me as living experience.”2

To discount the letters would be to neglect the existential basis or ground of Heidegger’s thought. Moreover, Heidegger’s correspondence includes exchanges with some of the outstanding figures in twentieth-century philosophy and letters: among them, Heinrich Rickert, Karl Jaspers, Rudolph Bultmann, Hannah Arendt, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Ernst Jünger, and René Char. In these cases, Heidegger’s letters are, quite obviously, of intrinsic philosophical and/or cultural significance.

Equally revealing are Heidegger’s epistolary exchanges with close friends and family members such as Elisabeth Blochmann, Elfride Heidegger (the philosopher’s wife), and his brother, Fritz. This is true insofar as, in the course of these colloquies, Heidegger often paused to shed invaluable light on the nature and substance of his philosophical trajectory. Lastly, such conceptual clarification is especially welcome in the case of a philosopher like Heidegger who, in keeping with his emphatic disavowal of “publicness,” inclined toward hermeticism.

As Heidegger avowed in Contributions to Philosophy (1936–38), “Only the great and secretive individuals ensure the stillness necessary for the advent of the god.”3 And in Anmerkungen I–V, he affirmed, “Whoever knows me only on the basis of my published work does not really know me at all.”4 Given Heidegger’s predilection for philosophical esoterics, the elucidations that the letters provide remain valuable and indispensable.”

Heidegger in Ruins: Between Philosophy and Ideology

+ Adolph Hitler the Progressive

+ The Evil of Banality: Troubling new revelations about Arendt and Heidegger (Slate)